What we’re seeing in macOS malware development is a reflection of how cybercrime itself evolves. As security ecosystems mature, threat actors are creating malware that is more efficient and more resilient than ever before. At Moonlock Lab, MacPaw’s malware investigators are already tracking what this evolution is shaping up to deliver in the year ahead.

In 2026, macOS won’t be an outlier for cybercriminals but a natural extension of attack operations already proven profitable on Windows and other platforms. Apple-notarized apps won’t necessarily be synonymous with safety. Infostealers will solidify their role as the primary on-ramp to extortion. And finally, large language models (LLMs) will facilitate the transformation of once-tailored attacks into repeatable workflows.

It all adds up to the fact that macOS malware won’t look like malware at all, at least not to the people encountering it. More often, it will look trusted, familiar, and routine—a distinct problem that Moonlock Lab will be investigating closely.

Below, we break down how each of these shifts is emerging in the wild, shaping the trends in macOS malware worth watching in 2026.

1. Automation becomes a pathway for attack

Generative AI already makes it easier to write malware, refactor modules, translate implants across languages, and iterate on phishing at greater speed. When it comes to Mac malware in 2026, AI won’t stop at accelerating attacker productivity—it will create bigger issues. Beyond automation platforms and agent tooling, large language models themselves are becoming part of the attack surface.

In 2026, we expect to see increased experimentation with LLM-injection techniques in which attackers manipulate the data that AI systems consume in order to influence their outputs. Unlike traditional prompt injection, which targets direct user interaction, these attacks operate one layer upstream, poisoning the information sources that LLMs summarize or recommend.

One example is the abuse of AI-generated summaries in search engines, such as Google AI Overviews. If attackers successfully inject malicious instructions, links, or recommendations into content that an LLM later summarizes, the AI may unwittingly act as a trusted distribution channel, sharing malicious commands, scripts, or download links as part of legitimate-looking answers.

AI expands risks across business workflows

As AI assistants become more deeply embedded in workflows, the risk extends further through the growing adoption of the Model Context Protocol (MCP).

MCP adoption is rising because it standardizes how AI assistants connect to tools and data sources. That convenience also represents a risk: misconfigurations and injection-style attacks can turn helpful assistants into data-leaking automation.

Consequently, we expect more incidents where the compromise isn’t a traditional “dropper -> implant” chain, but a workflow chain such as the following:

- A compromised MCP server (or poisoned tool) influences an agent’s behavior.

- A prompt-injection path causes exfiltration “through legitimate channels.”

- The attacker uses the agent’s granted permissions to reach SaaS, repos, ticketing systems, or cloud data.

This is not theoretical hand-wringing. Security researchers are already documenting practical MCP risk categories like prompt injection, tool impersonation/shadowing, privilege overreach, and exfiltration via normal tool calls.

For example, CVE-2026-21858 (“Ni8mare”), which was reported by CYERA’s researchers as a critical issue enabling takeover paths in exposed instances, highlights how n8n’s integrations can increase impact by touching Google Drive, OpenAI keys, Salesforce, IAM, CI/CD, and more.

Another key instance was documented by Endor Labs, in which an active supply-chain campaign targeted the n8n community node ecosystem. Attackers published malicious npm packages masquerading as legitimate n8n integrations (e.g., a fake Google Ads node). The node presented a credential form that looked legitimate, then exfiltrated OAuth credentials during workflow execution to the attackers’ infrastructure.

This last attack brings us to another trend in supply chains that we will see in 2026.

Supply chain attacks become the default access strategy

Supply-chain-meets-agentic tooling incidents involve poisoned dependencies that don’t just run code but change what an AI agent believes and does, making the intrusion harder to detect in logs. As a result, supply chain attacks are becoming the default access strategy, not a niche technique.

Supply chain attacks are moving upstream into the places where developers and operators “plug things in” quickly—nodes, packages, connectors, agents, and templates. The 2025 npm ecosystem compromise involving the self-replicating worm, publicly called Shai-Hulud, is the blueprint: It was spread by stealing credentials and then automatically publishing trojanized packages at scale.

Based on lessons learned so far, here are the key themes defenders should carry into 2026:

- Credential theft as propagation fuel (PATs, CI/CD tokens, cloud keys)

- Automation in the attack loop (rapid republishing, downstream infection)

GitHub’s response underscores where the ecosystem is heading: stricter authentication, better publishing controls, and more supply-chain hardening, but also an implicit acknowledgment that package registries are now an active battleground.

2. If 2025 was about scale, 2026 will be about staying invisible

As Apple continues to strengthen built-in protections and security vendors improve macOS detections, threat actors are responding in predictable ways: by leaning harder into Apple’s trust signals, fragmenting malware into quieter stages, and complicating analysis and attribution.

Malware gets signed and notarized

Attackers will continue to lean into Apple’s trust signals. Why? Because they work.

A concrete example was published by Jamf in December 2025: MacSync stealer delivery via a digitally signed and notarized Swift application masqueraded as a legitimate installer specifically to bypass Gatekeeper friction.

This aligns with the broader industry observation that the category of Apple-notarized malware is a growing issue, especially when the notarized app is a clean-ish stage that fetches or assembles the real payload later. For users, the implication is uncomfortable but clear: “Signed and notarized” no longer means safe.

Multi-stage delivery becomes standard

Modern macOS malware is increasingly designed around one goal: to shorten the time between user interaction and silent compromise.

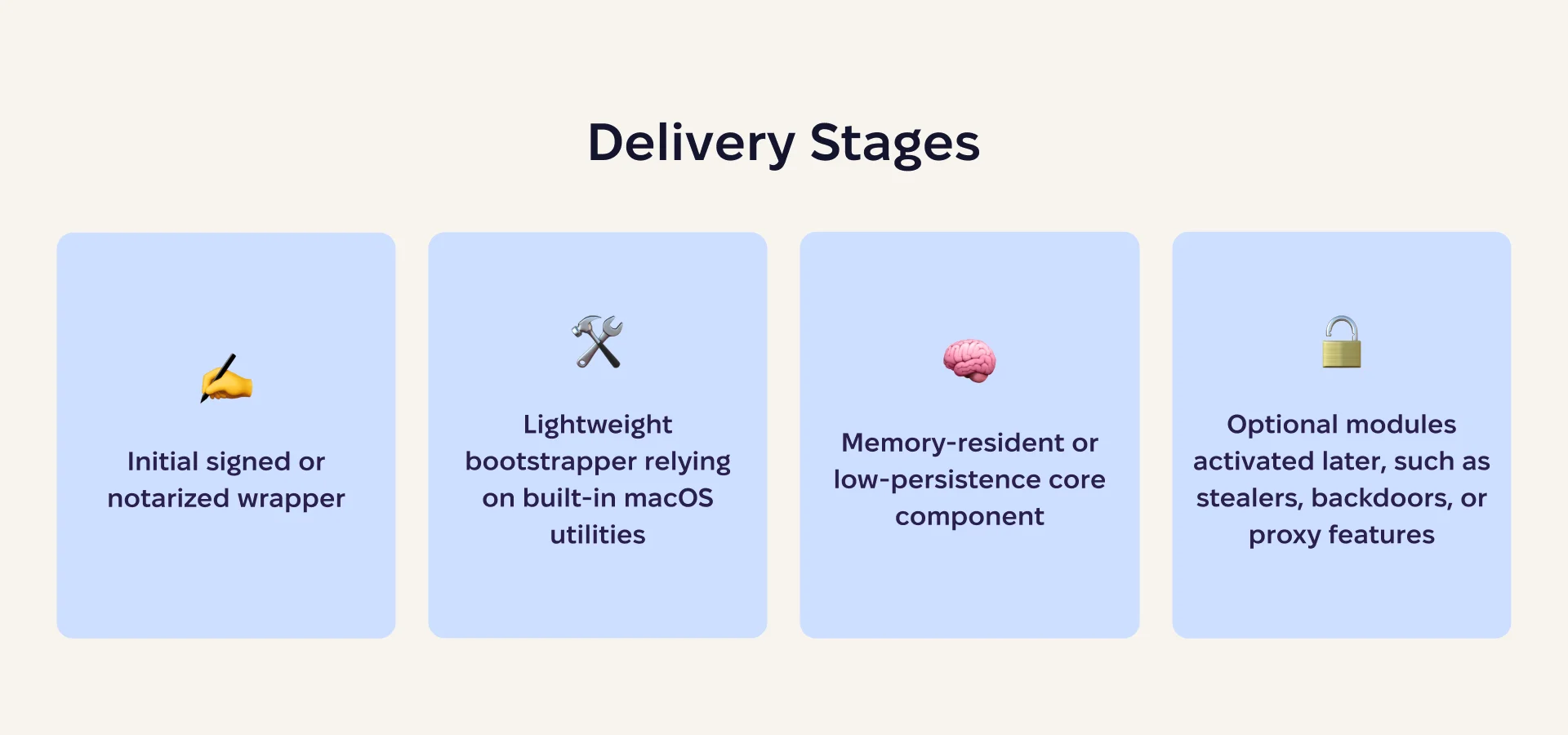

Rather than a single noisy execution step, attackers are shifting to layered delivery chains that distribute functionality across stages.

Newer macOS infostealers already reflect this trend, highlighting multi-stage behavior, anti-analysis checks, and low-footprint execution designed to evade both user awareness and security tooling. In 2026, we expect this approach to become the default rather than the exception.

Obfuscation and packing continue to evolve

At the payload level, the macOS malware arms race shows no sign of slowing down. Threat actors continue to experiment with script and binary obfuscation, including compiled shell scripts, heavily obfuscated Python, Go-based implants, and less common payload formats mentioned below—all explicitly designed to evade static detection and delay analysis.

Language diversification goes “weird”

Another anti-detection strategy gaining traction is language diversification. In recent years, macOS malware has expanded beyond traditional C/C++ into Go, Rust, Nim, and Crystal. And in early 2026, the community received another strong signal that attackers are experimenting beyond familiar territory.

In January, researchers @malwrhunterteam and @L0psec shared an analysis of an unusual macOS sample that appeared to be compiled with Zig—a language rarely seen in real-world macOS malware so far. The sample exhibited keylogging behavior, AES usage, and socket-related functionality, raising the question of whether it was a test binary, proof of concept, or an early-stage malware experiment.

Even if this particular binary turns out to be experimental or non-operational, it still matters.

macOS malware authors don’t need Zig to become mainstream for it to be useful. Its value lies elsewhere:

- Detection lag: Security products and heuristics are slower to adapt to unfamiliar compilation artifacts.

- Analyst friction: Reversing takes longer when decompilers misinterpret calling conventions, data flow, or symbol usage.

- Tooling asymmetry: Fewer mature signatures, fewer public writeups, and less shared tribal knowledge.

We’ve seen this pattern before with Nim and Crystal. Zig appears to be following the same trajectory, not as a replacement for Go or C++, but as a strategic option for loaders, packers, short-lived droppers, and niche tooling where stealth and novelty buy attackers time.

3. Compromised Macs will power malicious infrastructure

Avoiding detection is only half the equation. Avoiding attribution is the other. We highlighted this shift in 2025, noting that macOS infection increasingly means that the compromised system becomes part of a broader criminal network, often with proxy functionality baked in.

Using victim machines as traffic relays provides attackers with 2 key advantages:

- Attribution friction: Malicious activity appears to originate from legitimate residential or corporate IP spaces rather than attacker-controlled servers.

- Operational resilience: Even when command-and-control infrastructure is seized or disrupted, proxy meshes can reroute traffic and keep campaigns alive.

In 2026, we expect more macOS malware families to ship with optional proxy modules or integrate with existing proxyware ecosystems because it’s a cheap and effective way to buy operational security.

4. Criminal infrastructure moves to blockchain

Another trend gaining traction is threat actors moving their infrastructure to the blockchain. We already saw early versions of this in 2025, when DPRK-linked groups experimented with using blockchain and smart contracts as C2 channels.

While the groups adopting this model today mostly target Windows, we’ve seen this pattern before. Essentially, what works in Windows ecosystems tends to migrate to macOS.

The idea is simple: If there’s no server, there’s nothing to seize. No hosting provider, no domain registrar, no easy takedown. In January 2026, a ransomware group known as the_cry0 publicly announced that it was abandoning Tor in favor of blockchain-based infrastructure. Negotiation pages and victim chat portals would now be hosted on-chain. In other words, victims no longer need to use Tor—everything opens in a regular browser via a direct link. The group openly advertised the benefits: 100% uptime, DDoS resistance, and immunity to law-enforcement seizures.

From an attacker’s perspective, this makes perfect sense. Blockchain-hosted infrastructure removes single points of failure and turns extortion portals into something much closer to “permanent” services.

5. Infostealers are moving upmarket

The economics of cybercrime are shifting, and macOS malware is shifting with them. Extortion continues to outperform classic ransomware-only attack models. In 2026, we can expect the macOS stealer ecosystem to split further into high-volume commodity tools and operator-grade stealers built for corporate access and extortion workflows.

According to the Sophos Annual Threat Report 2025, encryption rates are falling as adversaries shift tactics. Among manufacturing organizations, only 40% of attacks resulted in data encryption—the lowest level observed in 5 years. At the same time, extortion-only attacks surged to 10%, up from just 3% in 2024, signaling a clear increase in attacks that rely solely on data theft and leverage rather than disruptive encryption.

By 2026, macOS stealers will increasingly target enterprise access, not just crypto wallets or browser passwords. Stolen credentials, tokens, and sessions provide leverage—either for follow-on intrusions or for resale to extortion and ransomware operators.

We already have strong evidence of this pipeline. KELA’s Analysis of leaked Black Basta chats showed ransomware affiliates using credentials sourced directly from infostealer logs as initial access, with thousands of credentials tied to sensitive enterprise systems.

For macOS specifically, “enterprise stealer” increasingly means harvesting:

- SSO sessions and authentication cookies

- Developer and CI/CD credentials

- Cloud and API keys

- Messaging and productivity app data

All this occurs while maintaining persistent backdoor access to keep harvesting data over time.

This also ties back to supply chain abuse. Credential-driven propagation was a core mechanism in the Shai-Hulud npm compromise, and similar patterns are likely to resurface.

6. Cross-platform cybercrime goes mainstream

One of the clearest signals heading into 2026 is that cybercriminals no longer treat macOS as a niche platform. Instead, it is increasingly being folded into large-scale, cross-platform operations originally built and funded around Windows malware.

This shift matches a broader economic reality: Many threat actors have accumulated capital, infrastructure, and operational experience through Windows-focused campaigns. As those operations matured, macOS became a natural expansion. The result is a growing number of campaigns where macOS payloads are just one component of a much larger criminal pipeline.

In other words, in 2026, many macOS malware campaigns won’t look “Mac-native” at all. macOS threats will increasingly mirror Windows trends, just on a slight delay, while benefiting from the same funding, tooling, and professionalization.

Final thoughts

If we were to define a theme for Mac malware in 2026, it would be subtlety. The development of malware is becoming less improvised and more professional, folding into large, well-funded attack pipelines. Malware is now being designed to blend in with macOS processes, move in stages, and exploit the spaces where average users and organizations assume that they are safe.

In an environment where malware is difficult to recognize, having extra eyes on the system is a must. At Moonlock Lab, we will continue to track threat actors and their ways of breaking through the safeguards. We’ll share more of our findings in the months ahead.

Meanwhile, everyone can turn Moonlock Lab’s research into practical protection with our Mac protection and antivirus app, Moonlock. With this additional layer of security, Mac users can quickly bring the subtleties to light before they become consequential.

This is an independent publication, and it has not been authorized, sponsored, or otherwise approved by Apple Inc. Mac and macOS are trademarks of Apple Inc.