Open-source malware hosted on GitHub is free to use and free to copy. It can be modified and customized, and it can be distributed to anyone. But while some malware repositories (project files and resources) are posted by GitHub users for education and research purposes, many others are designed to do damage.

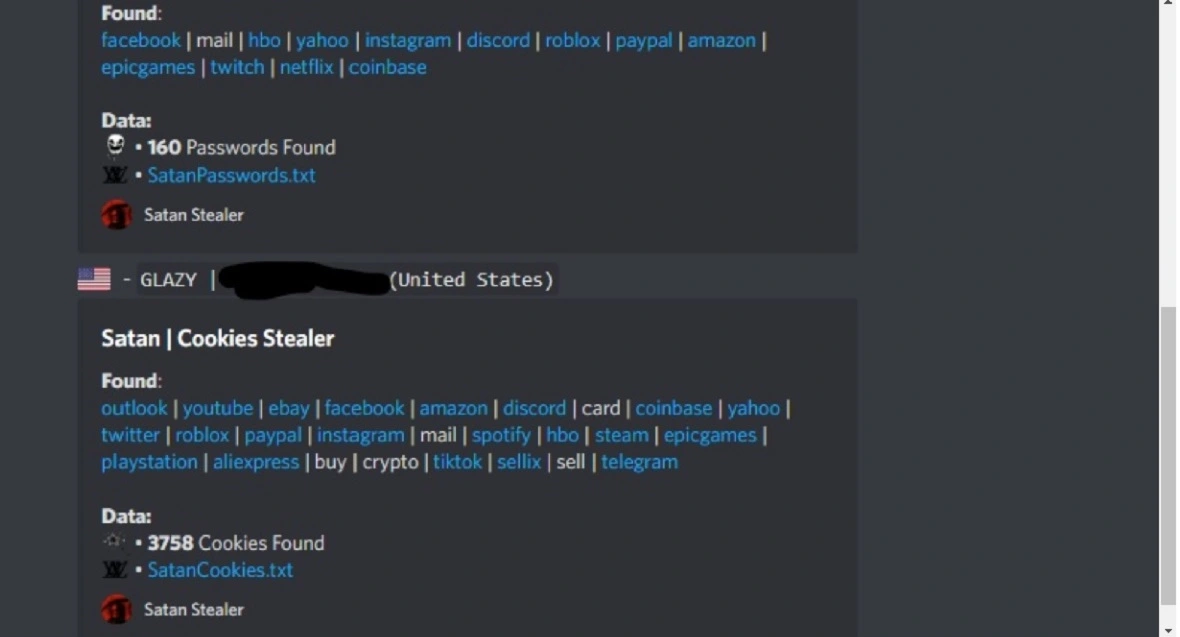

The new malware known as SatanStealer is one of the latter. SatanStealer can breach and steal Discord data, personal data, and contacts. Plus, it can grab browser cookies, passwords, special files, crypto wallet credentials, and more.

SatanStealar: A free threat available to anyone

On June 18, ThreatMon researchers first announced the discovery of a new stealer called SatanStealer through a post on X (formerly Twitter).

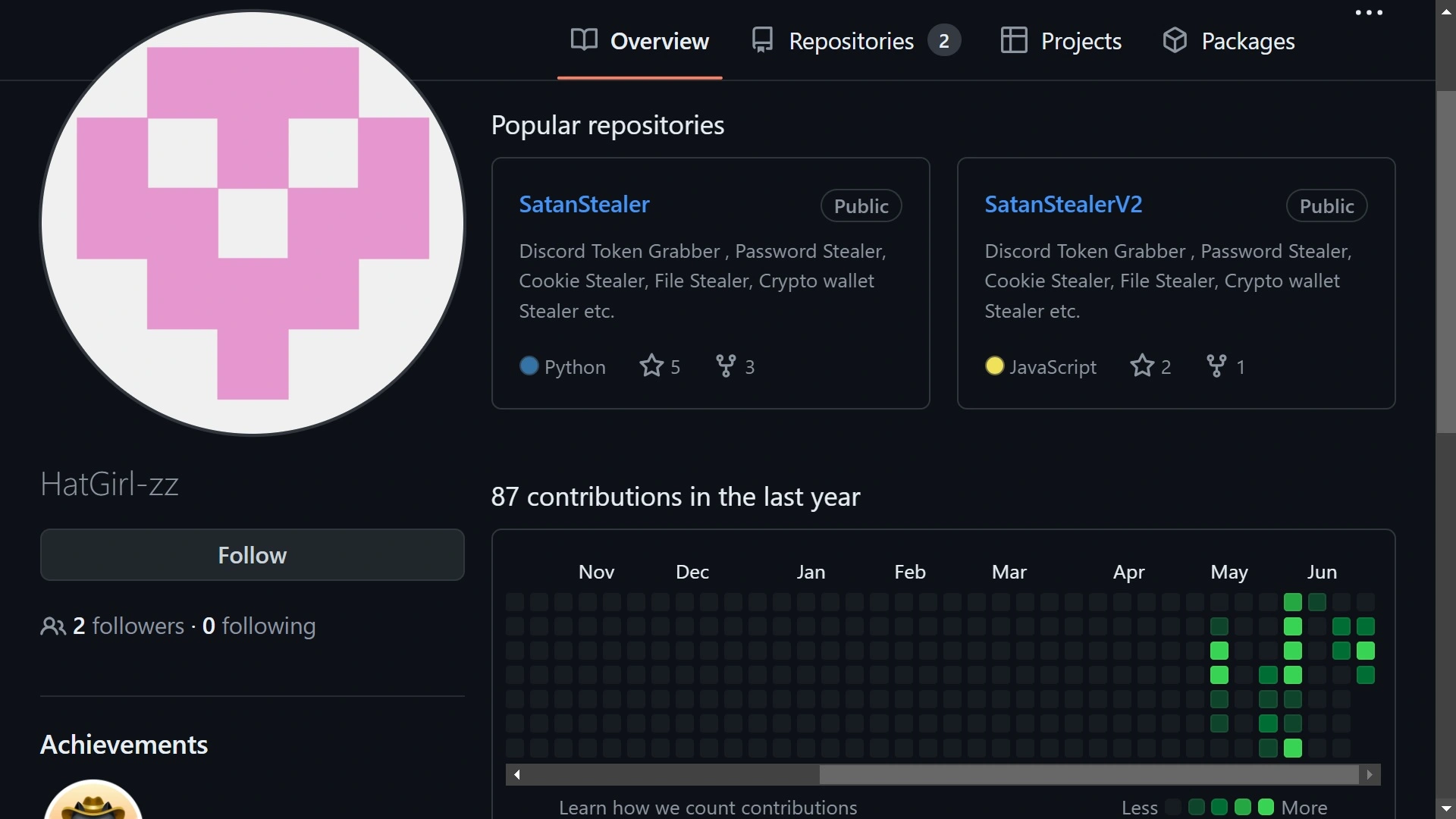

The malware was uploaded to the open-source platform by a GitHub user called HatGirl-zz. HatGirl’s account shows no activity until May 2024, when the first version of SatanStealer was released. Weeks later, the still-active account released a “better version”: SatanStealer2.

What can SatanStealer2 do?

HatGirl-zz claims SatanStealer2 is for “education purposes only and cannot be sold under the published license.” For open-source malware, however, SatanStealer2 is a rather sophisticated repository. Anyone can easily download the code. And thanks to the guides and readme files, users can simply follow detailed steps to launch attacks.

SatanStealer2 can target crypto wallets. However, unlike many crypto stealers, it targets some of the top names in the blockchain industry, including MetaMask, Atomic, Exodus, Binance, Coinbase, Trust, and Phantom crypto wallets.

The malware can also steal special files from victims and breach and steal Telegram and Discord information. It can also steal victims’ personal data, including phone numbers, email addresses, and contacts. Additionally, the SatanStealer can breach user browser functions and steal cookies and authentication data (usernames and passwords).

The stealer works on Chrome, Edge, Brave, Opera, and Yandex. To date, it cannot target Safari or Firefox. However, because it is open-source, it could be downloaded and customized to do so.

Attribution and motive: Who wrote SatanStealer, and why?

Regarding attribution, there is no geolocation data on HatGirl-zz’s repositories, nor are there comments in the code in any language other than English. Given the nature of GitHub, pinpointing attribution — who wrote and uploaded this code — and why this stealer was released is extremely challenging.

Recognizing benign versus malicious GitHub profiles

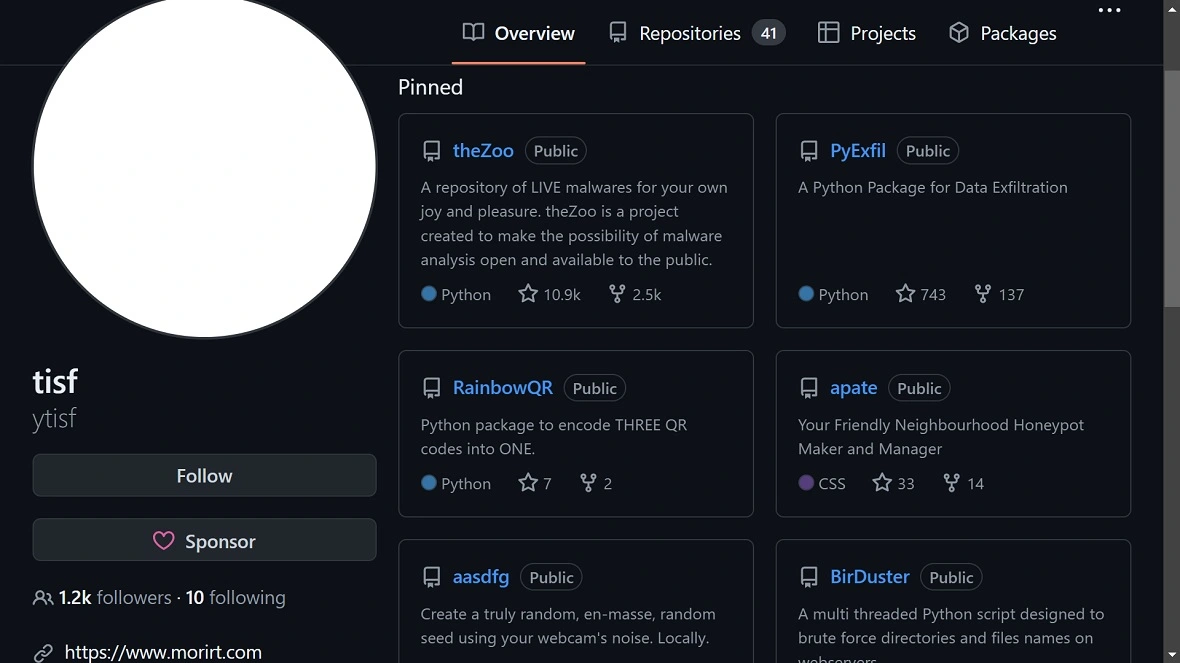

Malware samples on GitHub are, as mentioned, not uncommon. The community of developers shares samples to learn, investigate, and improve code, and for basic curiosity.

However, HatGirl-zz’s profile shares more similarities with cybercriminal profiles than it does with those posting malware for research and educational purposes on the platform.

Users who share malware samples for educational purposes are usually very active on the platform. They tend to have hundreds or thousands of contributions and have been on the platform for years. They usually also have hundreds or thousands of followers, and they tend to include their websites or social media links.

In contrast, HatGirl-zz’s profile is very different. The short paper “Who is Creating Malware Repositories on GitHub and Why?” by students of the University of California, Riverside, offers a good thesis. We can use this as a starting point to understand who is creating and distributing malware on GitHub and what their motives are.

“We find that malicious authors often have sparse profiles and focus on creating and spreading malware, while benign authors typically have complete profiles with a focus on cybersecurity research and education,” the paper explains.

HatGirl-zz’s profile shares all the characteristics of malicious malware distributors. The account has no history except for the past weeks, has no engagement and just two followers, and does not include user websites or social media links.

The dangers of rampant “confusion attacks”

While SatanStealer can be downloaded by bad actors to use in their attacks, it can also be used for something more sinister. GitHub repositories are leveraged by coders when developing new applications. Popular repositories with specific functions are the perfect shortcut to software development. They have proven performance. Plus, they’re free and popular. As a result, these codes often end up in hundreds of thousands of apps, websites, APIs, and digital environments.

Cybercriminals looking to cast wide nets will conceal malware in popular GitHub repositories, which then ends up in software that rolls out into the world.

A February Apiiro research found that malware in GitHub has been on the rise since mid-2023. Apiiro security research and data science teams detected more than 100,000 GitHub repositories that impersonate known and trusted repositories but are, in fact, infected with malicious code. The report estimated that millions of trusted repositories on GitHub are not malware-free. This trend is known as “confusion attacks.”

What are confusion attacks?

In confusion attacks, developers think they are downloading and using clean code, but in reality, the malware hides inside like a trojan executable waiting to run. Following this trend, SatanStealer could be integrated into these fake repositories.

Confusion attackers have cloned popular repos such as TwitterFollowBot, WhatsappBOT, discord-boost-tool, Twitch-Follow-Bot, and hundreds more. They download the original repo, infect it with malware loaders, upload them back to GitHub with identical names, and covertly promote them across the web via forums, Discord, and other channels.

SatanStealer and its ability to collect login credentials from different apps, browser passwords and cookies, and other confidential data, makes it ideal for confusion attacks.

Conclusion

Free, open-source malware like SatanStealer highlights the dangers lurking on GitHub. This malicious code can steal a wide range of personal data, including:

- Login credentials from various apps (Discord, Telegram)

- Browser cookies and passwords

- Crypto wallet details (MetaMask, Binance, etc.)

- Phone numbers, emails, and contacts

While the malware author claims it’s for educational purposes, its capabilities and lack of user identification suggest malicious intent.

The biggest concern is confusion attacks. Cybercriminals can inject SatanStealer into popular GitHub repositories, tricking developers into unknowingly using infected code. This can spread malware across countless apps and websites.

Stay vigilant and be cautious when it comes to downloading code from unknown sources, even on GitHub.

This is an independent publication, and it has not been authorized, sponsored, or otherwise approved by GitHub, Inc. GitHub is a trademark of GitHub, Inc.