A new investigation from ESET has found the first AI ransomware. Moonlock spoke to ESET to get the inside story and learn how the malware works, what it can do, and what Apple users need to know today.

Moonlock talks to the ESET Senior Researcher who analyzed the first AI-powered ransomware

On August 26, ESET reported that its researchers had uncovered a new type of ransomware. This malware uses GenAI to run its attacks.

Dubbed PromptLock by ESET, the ransomware uses a large language model to dynamically generate malicious scripts to search for files, steal them, and encrypt them. The malware can breach Windows, Linux, and macOS operating systems.

“During infection, the AI autonomously decides which files to search, copy, or encrypt, marking a potential turning point in how cybercriminals operate,” ESET said.

During infection, the AI autonomously decides which files to search, copy, or encrypt, marking a potential turning point in how cybercriminals operate.

ESET

Naturally, after reading this report, we had a lot of questions.

Fortunately, Senior Malware Researcher from ESET, Anton Cherepanov, was there to answer them.

An AI ransomware that mutates its IoCs

Given the little information available about this new AI ransomware, our first question went right to the core. We wanted the specifics and the nitty-gritty of how this ransomware works. Interestingly, we learned that the AI ransomware can mutate its IoCs when running attacks.

“PromptLock uses Lua scripts generated by AI, which means that indicators of compromise (IoCs) may vary between executions,” Cherepanov said. “This variability introduces challenges for detection.”

If properly implemented, such an approach could significantly complicate threat identification and make defenders’ tasks more difficult, Cherepanov explained.

Is PromptLock running amok in the wild?

Our next question for Cherepanov was one that is vital for the cybersecurity community and for users. Is PromptLock already in the hands of cybercriminals? And is it being used to target companies, encrypt their data, and demand a ransom in return?

Cherepanov explained that the ransomware they analyzed was a research proof of concept and not operating in the wild. Then he spoke about who discovered the ransomware.

Samples of PromptLocker on VirusTotal closely resembled the malware variant detailed in an academic paper titled, “Ransomware 3.0: Self-Composing and LLM-Orchestrated,” Cherepanov said.

The academic paper cited above was submitted on August 28, 2025, while ESET published its first analysis of PromptLocker 2 days before that, on August 26, 2025. ESET validates their discovery and the assumption that PromptLocker is, in fact, a proof of concept, a demo.

But if the ransomware isn’t being used in cyberattacks, does that mean it will not be deployed by threat actors?

“Deploying AI-assisted ransomware presents certain challenges, primarily due to the large size of AI models and their high computational requirements,” said Cherepanov.

However, it is possible that cybercriminals will find ways to bypass these limitations, Cherepanov said.

“As for development, it is almost certain that threat actors are actively exploring this area, and we are likely to see more attempts to create increasingly sophisticated threats,” Cherepanov added.

What can PromptLock do?

According to Cherepanov, PromptLock currently offers several options:

- Exfiltrate files

- Encrypt data

- Destroy files (though this last function does not appear to be fully implemented yet)

What part of the first AI ransomware actually uses AI?

These days, everyone online claims to be using AI. As such, understanding exactly what is AI-powered is fundamental. We asked Cherepanov if AI had been used to develop this malware.

“We are not certain that the malware itself is generated by AI,” Cherepanov said. “However, it does use scripts generated by AI, which means that IoCs may vary from one execution to another.”

Running on a “locally” accessible AI

ESET’s PromptLock analysis found that the malware runs a “locally” accessible AI language model. As mentioned above, it does this to generate malicious Lua scripts in real time. These are compatible across Windows, Linux, and macOS.

But what does “locally accessible” mean? In this context, “locally” means that the PromptLock malware doesn’t use APIs provided by cloud services like Gemini, OpenAI, Claude, or similar platforms, Cherepanov explained.

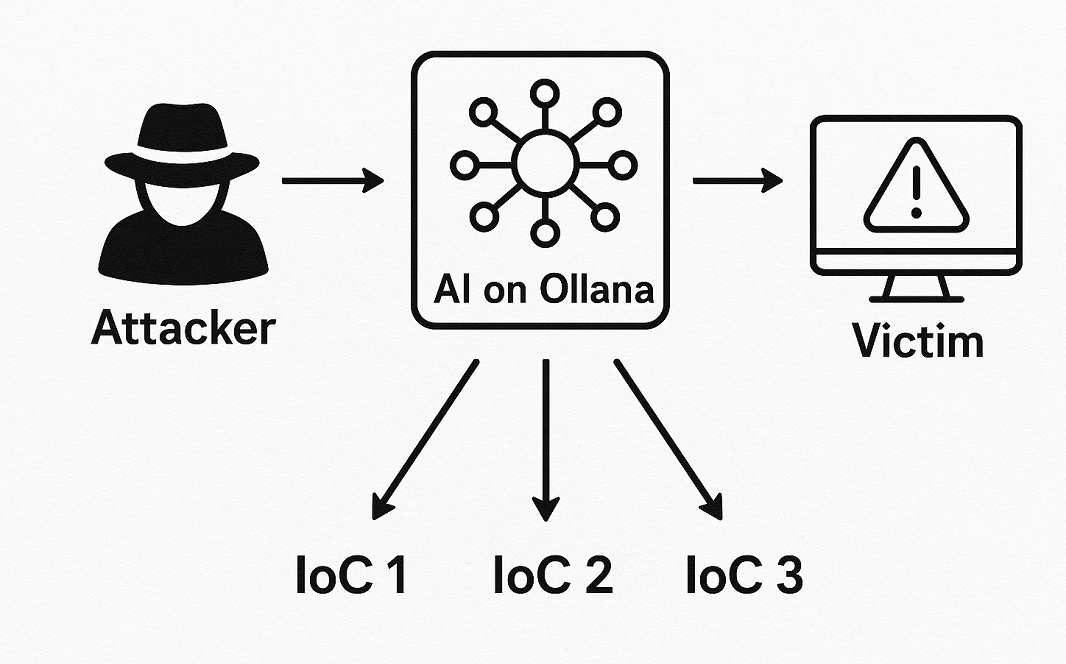

Instead, the attackers run their own Ollama server and make it accessible to the infected machine, he explained.

AIs on Ollama can act as “Ransomware attack chain middlemen”

An Ollama server lets users run open-source GenAI models like Llama, Mistral, or Gemma locally on their own computers. This eliminates the need for complex setup or cloud access.

“The PromptLock malware sends requests using the Ollama API to a computer within the same network,” he said.

This means that PromptLocker is prompting an AI on Ollama to generate code it will use to execute its attack.

Elements in this AI ransomware model include:

- Victim Device: the infected machine running PromptLock.

- PromptLock Malware: AI ransomware

- Local Ollama Server: hosting open-source GenAI model (in theory, other similar AI services could be used)

- AI Model: In this case, the model is gpt-oss-20b, but other lightweight models could be used to generate code for malware

- Generated Code: Sent back for execution

- Ransomware Execution: Final attack on the victim device

- Attacker Machine/Network: Connected to Ollama server

- Proxy Tunnel (Optional): An Indirect route used by the attacker to access the Ollama server

- Network Connection: Links all elements

As shown in the graph, the attackers can reach the Ollama server directly from their machine or network. They can also use a proxy tunnel, which is a hidden or indirect route that forwards their requests to the server, making it harder to trace or block.

“Attackers prefer running models locally via Ollama because it gives them full control, avoids provider oversight, keeps the model static and predictable, and makes bypassing safety features easier,” Cherepanov told us.

As mentioned, in the case of the ransomware variant of PromptLocker analyzed, the attackers were using the gpt-oss-20b model from OpenAI. The models are customizable. They are typically much more lightweight and deployable on local hardware than cloud-only models like ChatGPT‑4 or 5.

Ransomware key features: Lateral movement and privilege escalation

Cherepanov also highlighted that PromptLocker seems not to have lateral movement features or the ability to escalate privileges. These features are vital in modern ransomware attacks.

In modern attacks, attackers usually gain control over multiple machines. They use lateral movement to expand access, often escalating privileges to obtain domain admin rights.

“Once inside, they can install any malicious tools they need to carry out their objectives,” Cherepanov said.

Talking AI ransomware code with cybersecurity experts: Go and Lua

ESET’s analysis of PromptLocker also found that the variant was written in Golang and the AI-generated Lua scripts. But why these programming languages and scripts and not others?

We asked cybersecurity experts Amy Mortlock, Vice President of Marketing at ShadowDragon, and Dillon Rangel, Sr. Security Analyst at Framework Security, for their insight.

“Lua was chosen for its lightweight nature, cross-platform compatibility, and ability to run on Windows, Linux, and macOS,” Mortlock said. “Golang is used for the main ransomware code, as it compiles easily for multiple systems and is popular for its efficiency and flexibility among attackers.”

Rangel from Framework Security agreed that Lua is lightweight and portable. It is also easy for an AI model to generate correctly, Rangel said.

“One script works across Windows, Linux, and macOS,” Rangel added.

When answering why Golang would be used, Rangel said, “Modern malware authors love Go because it’s cross-compilable, statically linked, and bloated binaries are harder to reverse. It makes it trivial to ship one codebase across platforms.”

This means that with Go, malware authors can write their program once. They can then easily compile it to run on multiple operating systems (Windows, Linux, macOS) without rewriting the code.

In other words, the same Go code works everywhere, which saves time and effort when targeting different machines.

Apple users, heads up: Here’s what you need to know and how to stay safe

Finally, for Apple users who have stuck with us until the end of this report, hoping to get some advice on how to stay safe from this type of rather scary AI ransomware, here’s what we’ve got for you.

First, the good news. Fortunately, macOS makes it more difficult for ransomware to run autonomously. This is because Gatekeeper enforces developer code signing and, for software distributed outside the App Store, requires Apple notarization before allowing execution, Cherepanov told us.

“However, execution may still occur if the user overrides Gatekeeper or if malware exploits known vulnerabilities or evades the notarization process,” Cherepanov added.

This means that your built-in Apple security, Gatekeeper, is likely enough to keep you safe from this type of AI ransomware, as well as other nasty malware.

However, at Moonlock, we have been witnessing new techniques used by cybercriminals in the wild to bypass Gatekeeper. These include, for example:

- ClickFix attacks: Cybercriminals convince you to run scripts on your terminal by following malicious and fake step-by-step instructions.

- Second payload trojan downloads: Cybercriminals first convince you to download software that works as promised. However, when you install it, it modifies your system to download a second payload by triggering Gatekeeper alarms.

- Phishing via fake system prompts: Attackers trick users into entering their passwords or approving system changes by showing fake macOS alerts. These alerts look like legitimate security prompts.

- Zero-day attacks that exploit vulnerabilities: Attackers can target known security flaws in macOS that haven’t been updated yet. This allows malware to execute or escalate privileges without triggering Gatekeeper.

While this type of AI ransomware still isn’t being used by criminals, the techniques we describe above are very much in use. In fact, they are becoming popular when targeting Apple users.

To stay safe, avoid following instructions that ask you to copy code into your terminal or make changes to your system. Also, stay clear of suspicious messages and shady sites that offer free or cracked software. And double-check URLs to make sure you aren’t dealing with impersonators.

Only download software from Apple’s official App Store and keep your devices up to date with the latest patches to be on the safe side of zero-day attacks.

Final thoughts

This new AI ransomware proves that AI malware, coming our way fast, is much trickier than we originally imagined. As Rangel told us, every company hit by this style of attack would have a different, AI-generated version of ransomware, complicating analysis and recovery.

While this AI ransomware variant is far from operational, it does point us toward a messy ransomware and malware future — a future where the work of cybersecurity researchers and those who work to shut down cyberattacks and scammers in the wild becomes even more complex than it already is.

This is an independent publication, and it has not been authorized, sponsored, or otherwise approved by Apple Inc. Mac and macOS are trademarks of Apple Inc.